The bulk of human activity is the creation and movement of information. Twenty years ago the Internet used zero percent of human energy consumption. Today, the digital economy uses ten percent of the world’s total electricity. This is the same amount that was used to light the entire planet in 1985.[1] Never has there been access to as much information and never has this information been as unreliable. Louise Bennett’s exhibition All at Once, featured at Media Arts Asia Pacific, explores screen-based mediation as an unstable fluid space of rainstorms and unpredictable futures. This exhibition investigates the emotional, spiritual and technical changes to our planet and to the structure of our brains, rewired by the Internet.

In an age where every notion can be observed and recorded, Bennett investigates the conditions of mediated disengagement as the content of her exhibition. The question of what digital media is and what the moving image does, is made central to Bennett’s enquiry. Four separate artworks occupy the gallery and spill out into the parking space. Each piece individually exposes the technological processes behind video itself. White Noise, a single channel video, looped and displayed on a small screen, hovers in the entrance of the gallery. The footage takes us on a journey by foot through a familiar and busy inner Brisbane setting. Suspended center stage, the artist’s hand holds a blank white card, deliberately obstructing our view and undermining the role of the camera to capture and record. Informed by monochrome abstraction and comparable to the surface of a painting, the card both conceals and seduces us via technical illusion. Glowing green pixels dance and distort the card’s surface, drawing the eye inward, distracting us from the infinite details passing by in the peripheral landscape. 5

The colour effect employed in this work is used by the moving image industry to create Chroma key, a post-production technique for removing the background and layering footage. White Noise embraces post-production, not to enhance or heighten an everyday experience but as a material intervention and as a means of creation. Here, the effect functions as a visual defect to disrupt and distance us from the landscape. The persistence of the artist’s hand reveals technology as both a post-human other and a part of everyday life. The experience of this work gives way to a subtle yet persistent anxiety that references the familiar mental state of multitasking. As we struggle to know where to focus, we are reminded of the tireless interruption and our incessant preoccupation with personal electronic devices. The mild anxiety generated by the work, combined with the enticement of its digital illusion draws upon a deeper, spiritual distress within our culture. Technology is disrupting our increasingly unfulfilled desire to be present in the moment of experiencing. 5

If White Noise refers to the history of monochrome painting, then Border Town, a small screen-based single channel video work, refers to Optical painting through its mesmerizing hypnotic effect and psychedelic sensibility. Framed by the architecture of the neighbouring building, Border Town is made up of multiple layers of the same footage played out simultaneously. Each video layer is slightly smaller than the layer behind it and the top layer in the center of the screen is imperceptibly small. Despite the repetition of the image, the viewer is continually denied a complete view of the whole image at any time and the eye is repetitively drawn to the center and then pushed back out to the peripheral in search of the missing visual information. 2

This emphasis on our peripheral vision is employed as a metaphor for our collective lack of ability to focus. Even when disengaged from an electronic device, fractured thinking and lack of focus persist. Neuroscientist Adam Gazzaley said “the non-stop interactivity is one of the most significant shifts ever in the human environment.” 3 Border Town acknowledges the ambivalent position of technology in our culture and its effect on mental processing. Despite the small amount of information received in the bordering edges of this layered video work, the artist provides us with a sense of travelling at a high speed through a landscape, highlighting the increased pace of life in our mediated culture.

Our sense of time is beginning to shrink … we’ve tampered with the old-fashioned organic perception of time … and it’s not just because you’re older and each year is a smaller percentage of your life … it’s simply moving more quickly. 1

The notion of travelling is consistent in the installation work Plasticine Landscape. A small, framed image, situated directly opposite Border Town, depicts a landscape divided by a road that disappears into the distance. The artwork is suspended in the garden surrounding the gallery and is lit by the artists’ car lights. The car parked in front of the work, its headlights left on, sets the tone for the entire exhibition. We get a sense of viewing the image through the car windshield, as it blocks our ability to stand directly in front of the image. The notion of a detached experience finds its most fluent expression and closest association in daydreaming whilst driving a car. Again, in the center of the landscape, a white card obstructs our view. This time with the handwritten text “please remember me”. This sentiment explicitly refers to our waning ability to remember, whilst evoking a sense of nostalgia and loss of the landscape itself. All the while, we view this work with an understanding that the car’s battery is slowly dying. This disrupts our ability to remain present and mildly disturbs our experience with a subtle anxiety about the future. What is set up is a circumstance under which the allied categories of emotion and the machine converge. 4

We find ourselves in a cultural moment where depth is replaced by surface and simulated affects replace real ones. The video work Brisbane Hail Storm, featured in the main gallery space, is a reflection of this moment. Upon entering this work, the viewer is engulfed by the loud surround sound and large-scale projection. The work is composed of found footage that beautifully captures the recent and violent ‘freak’ storm that hit Brisbane CBD in November 2014. Although not immediately detectable, the found footage is recontextualised from the Internet. The pixelated distortion of the footage dilutes the terror of the lived experience. However, this deliberate formal characteristic preserves the anxiety caused by the hailstorm by foregrounding the role of technology in today’s unpredictable climate.

The carbon that fuels our electronic life is melting the ice caps. The shifting weight of million of billions of tons of melting ice is relieving vast gravitational pressure from the Earth’s crust. 1

This digital video work exclaims that Brisbane’s ‘supercell’ storm of 2014 is no coincidence! Whilst the work takes us on a self-reflective journey into the conditions of our extreme present and our part in it, gradually and curiously, the camera pans out to reveal a view of a monitor that is playing the storm footage. This presents us with multiple degrees of mediation. We hear birds chirping, a flood of calm washes over the room, the monitor blurs and the dramatic sounds of the hailstorm fade into the background. Our awareness of our present experience of engaging with the work becomes heightened as it is brought into focus. With a sudden jolt the camera is directed outside at a single view of Brisbane city from an elevated position, in gorgeous soft pastel hues, the sun rises.

The dynamic of this switch in our focus and perspective is central to our understanding of how mediated experiences have become intertwined within the fabric of our lives. Bennett invites us to meditate on the surround sound of lived and embodied experience, providing us with the space to reflect upon the technological conditions of our culture. Consistent across each of the artworks featured in this exhibition, the subject matter becomes physical verses digital encounters as well as the complication and interconnection of these modes of experiencing. 2

These works do not converge at a single decisive point but rather continually circle, reveal, challenge and embrace the formal strategies that characterise the medium. This exhibition reveals the capacity of the digital moving image to migrate and shift between real experiences, online spaces, computer monitors and immersive environments All at Once. In doing so, the artist highlights the absence of a consistent and uniform boundary between embodied, remembered and mediated experiences within our contemporary digital age and the myriad of ways this is transforming our experience of the present and redefining our future. 1

Written by Michelle Eskola, (2015)

[1] Basar, S, Coupland, D, Ulrich, O (2015) The Age of Earthquakes – A Guide to the Extreme Present, Blue Rider Press, USA

2 Campian, D (2013) Converging Perspectives, Accessed June 8th 2015, from

http://paper-journal.com/interview-johan-rosenmunthe/

3 Richtel, M (2015) Attached to Technology, Accessed June 8th 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/07/technology/07brain.html?_r=0

4 Shinkle, E (2010), Video Games and the Technological Sublime, Accessed June 8th 2015, from http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/video-games-and-technological-sublime

5 Steyerl, H (2015) Too Much World – The Films of Hito Steyerl: Is the Internet Dead?, Sternberg Press, The Van Abbemuseum and The Institute of Modern Art, Australia

For the exhibition – Louise Bennett: All At Once – 22nd May – 26th June @ MAAP SPACE

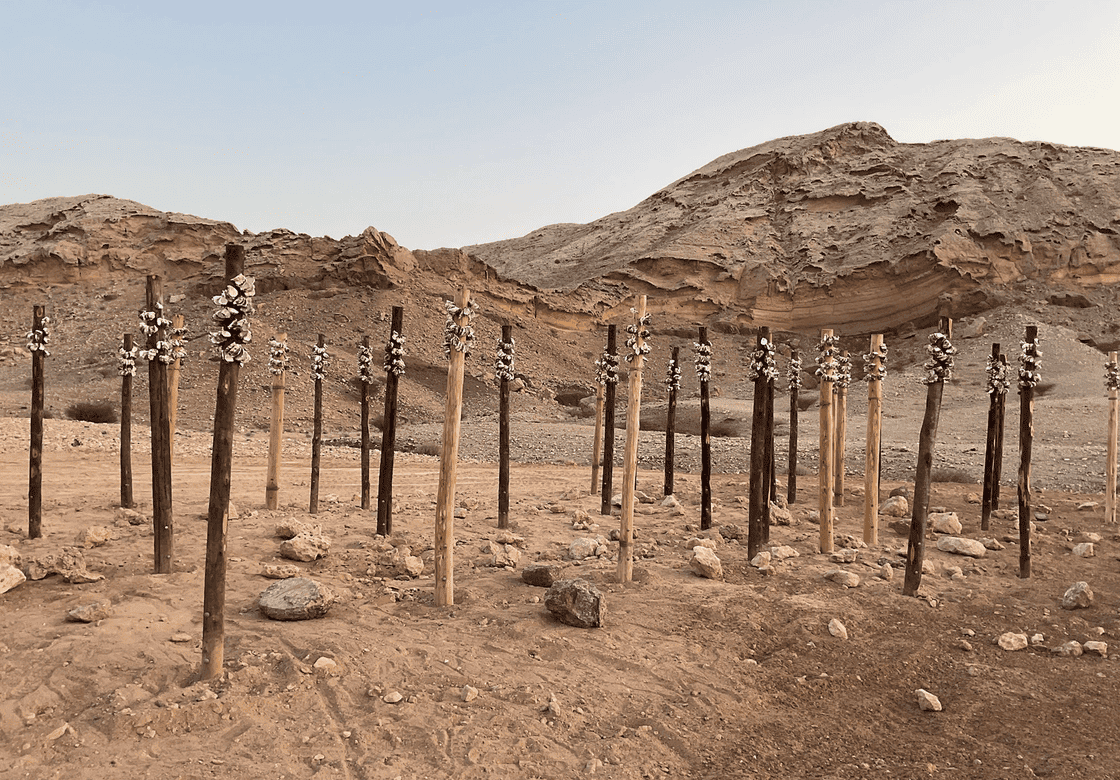

Image: Louise Bennett, Brisbane Hail Storm (2015)