Time is a fundamental and axiomatic philosophical concept that has long been a chief subject in several areas of study. Numerous different values, meanings and ideologies can be linked to it, which makes defining time in a universally acceptable manner quite difficult. This is never more true than in Australian Indigenous culture, where their concept and portrayal of time in their artworks remains a subject that is widely debated, even today. Conventional understandings of the concepts of Indigenous time do not, unfortunately, provide a thorough insight into the portrayal of said ‘time’ in Indigenous artworks. Consequently, the representation of time in Indigenous artworks remains somewhat ambiguous. However, the relationship that Indigenous artists share with their land, illustrated in their artworks, is undeniable. Through an analysis of artworks by renowned Indigenous artists Emily Kame Kngwarreye, John Mawurndjul and Rover Thomas, I aim to examine these artist’s potent connection to ‘place’, steering the focus of interpretation away from a purely temporal reading of Indigenous artworks.

Before examining proposed concepts of Indigenous time, one would have to gain, at least, a general understanding of Indigenous culture and ontology. As observed by Australian anthropologist, Lynne Hume, Indigenous cosmology is “centered on The Dreaming”[1], which, often referred to as the ‘Dreamtime’ or ‘everywhen’ to its express its timelessness, embodies their entire being. It is the sacred wisdom, moral truth and understanding of their Country that is altogether derived from Dreaming events and stories. The land where their mother feels the first signs of pregnancy determines each Indigenous person’s Dreaming and totem. At this location, the child receives the spirit of a totemic ancestor, for example, a possum or honey ant, and the Dreaming akin to that place.[2] The question now arises as to how these spiritual and cultural concepts are transferred, if at all, onto Indigenous people’s artworks. Associate Professor of Middle Eastern and Mediterranean history, Dr William Gallois, encourages his readers to contemplate how the Dreamtime of Aboriginal people or Buddhist interpretations of ’no-time’ might shed some light on a human history of the world.[3] He begins his study with the argument that “we live in different times” and attempts to persuade the “obdurate historians in the West” who (apparently) privilege their idea of linear time, to picture time, and all beings in time, as a fluid and ephemeral.[4] A possible reason behind this shift away from a ‘traditional’, Western understanding of time could be, as Dr Brian Edgar concludes, due to Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity.[5] Einstein’s relativistic view of time demonstrates that time is not absolute and cannot be comprehended in an “objective, objectified and, ultimately commodified manner.”[6] Instead, it allows for a reading of time as a sequence of personal activity, which Edgar likens to Aboriginal Dreamtime. He suggests that Indigenous Australians do not view time as a horizontal series of pasts but rather as a vertical relationship to the present, a “sacred-past-in-the-present.“[7] Edgar, however, is not the first to propose an understanding of Indigenous philosophies of time and the subsequent effects of such on their daily lives.

Distinguished author, Tony Swain, in his seminal book ‘A Place for Strangers’, examines attempts made at understanding time in Aboriginal philosophy and the challenges of academic preconceptions of time. Swain begins his study by acknowledging the work of influential Australian anthropologist, Adolphus Peter (A.P) Elkin whom, in Swain’s opinion, made the first serious attempt to understand Indigenous concepts of time. Elkin argues that for Indigenous people, time is current, where “then is a past…the past, however, is present, here and now.”[8] Swain goes on to explore the work of William Edward Hanley (W.E.H) Stanner, another prominent Australian anthropologist who worked extensively with Indigenous Australians. In his famous article ‘The Dreaming’, Stanner examined the relationship between Dreaming and time, coming to the conclusion that the Dreaming could not be ‘fixed’ in time as “it was, and is, everywhen.”[9] Therefore, from the somewhat varied opinions of Indigenous time mentioned above, where some academics argue that Indigenous time flows vertically, while others argue that it cannot be quantified period, it can be deduced that a single, definitive definition of Indigenous time does not exist. Due to this ‘problem’ of expressing Indigenous understandings of time as embossed in Dreaming and in general, Swain asserts that he is not surprised “to find scholars either avoiding definitions completely or attempting to dress obscurity in poetic guise.”[10] What is perhaps most striking about Swain’s argument is his rejection of a binary view of temporal constructions, where he denounces academic preconceptions of time. He argues that a largely unchallenged assumption in the field of academia remains that if time is not linear, then by default, it must be cyclical. This, Swain argues, is what he believes has lead academics to presume that Indigenous understandings of time run in cycles.[11]

This remains true today, where contemporary art institutions such as the Harvard Art Museums, refer to time in Indigenous society as a “cyclical and circular order”,[12] suggesting that their conceptions of time is reliant on encounters with their natural and ancestral worlds. The problem with this view, Swain reasons, is that a circle is, in essence, a line that returns upon itself. Hence, if a linear representation of time requires an application of quantifiable numbers, circles too would revolve around according to a numeric sequence. In order to combat this approach, Swain encourages people to stray away from a “two-candidate typology”[13] and instead, allow conceptions of Indigenous time to be understood on their own terms. One way to do this would be to examine the intense connection that Indigenous people share with their land. In some cultures, ‘place’ is of paramount significance to the people, more so than time. Their land ties them to their elders, gods and heroes in a manner that time cannot. It is not possible for Indigenous people to go back in time and live with their ancestors, but it is possible for them to visit the land where these events occurred, where their ancestors lived. As a result, the present mingles with the past, where the land, as argued by Edgar, “embodies the Dreaming, and it thereby connects time to place.”[14]

Quite often, Indigenous artists create artworks that are visual representations of the symbols affiliated to their Dreaming, and therefore, their Country. One such example would be the works of acclaimed Indigenous artist, Emily Kame Kngwarreye (1910-1996). Although Kngwarreye did not take up painting until much later in life, she was not new to artistic expression as she was exposed to a lifetime of ritual and artistic activity via the desert and body paintings for the Awelye song and dance ceremonies; Awelye being the word for women’s ceremonies and the specific designs applied to women’s bodies as part of a ceremony. In this way, Kngwarreye’s artworks resonate these ceremonies, celebrating her land, Alhalkereand her totems, kame (the yam) for which she was responsible.[15] Her painting, ‘Emu Woman’ 1988-89, is celebrated as her first major painting on canvas and was part of the first community-wide painting project administered at the Alice Springs-based Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association. The harmonious interaction between the warm and cool colours along with the innovative application of ‘dotting’ in Emu Woman signaled an unambiguous departure from the ‘dot and circle’ style of the, at the time, male dominated desert art movement. Almost immediately, this painting and the aesthetically vibrant hues, dotted along the surface of the canvas, encapsulate its viewer. Aside from the lively interaction between the coloured dots across the frame, there is also a sense of an underlying narrative present in ‘Emu Woman’, partially concealed on the surface. Her profound connection to Country and spiritual symbols is unveiled via painterly gestures that mimic the contours of body paintings and the designs made on women’s breasts for ceremonies. These gestures, though fairly abstract, along with the plants and seeds depicted in this work, bring out a raw energy in the painting that pays homage to Kngwarreye’s Dreaming and the Emu ancestor. When interviewed about the meanings of her paintings, regardless of which painting it was, Kngwarreye always had the same answer:

“Whole lot, that’s whole lot, Awelye (my Dreaming), Arlatyeye (pencil yam), Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), Ntange (grass seed), Tingu (Dreamtime pup), Ankerre (emu), Intekwe (favourite food of emus, a small plant), Atnwerle (green bean), and Kame (yam seed). That’s what I paint, whole lot.”[16]

In other words, her art was solely tied to and informed by her connection to her community and Country, rendering her art and life inseparable. Through the analysis of her artwork, it is not clear if Kngwarreye had a clear agenda of expressing the temporal factors of her being in her artworks. What is clear though, is regardless of material or scale, it was always the depiction of her Dreamings and Country of Alhalkere that stood out as her cultural legacy, which she kept alive in her artworks.

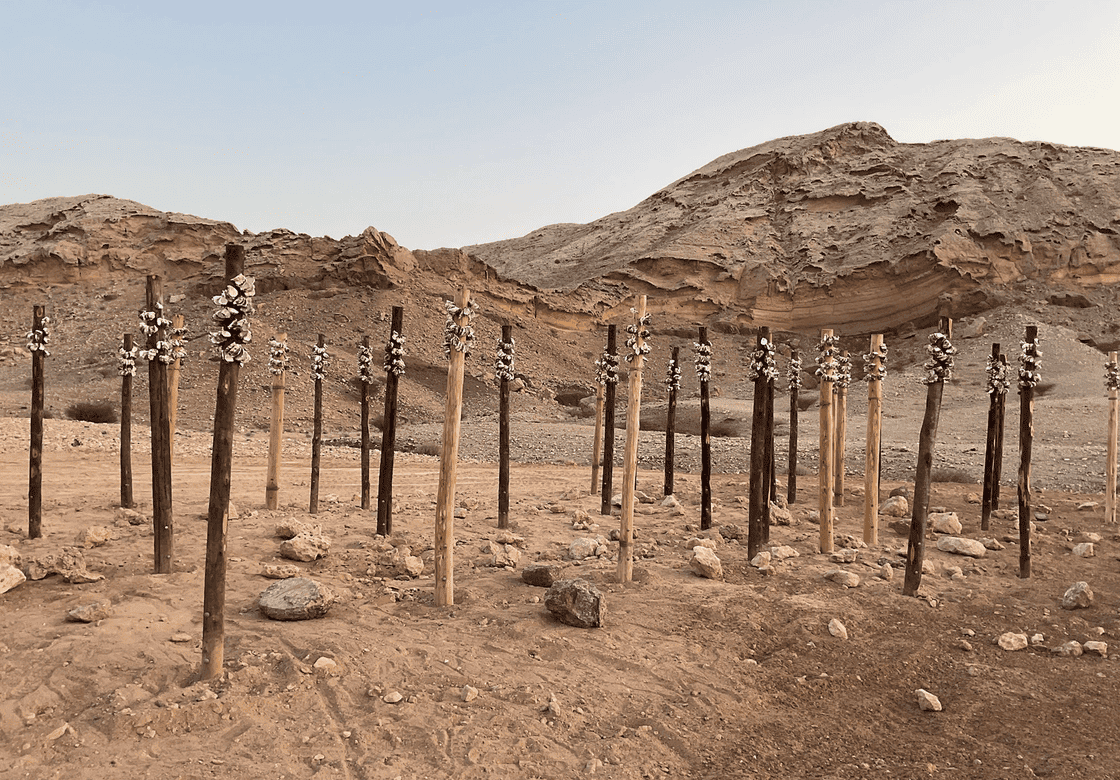

John Mawurndjul (born 1952) is a contemporary Indigenous artist who is arguably one of the most experimental and influential bark-painters of Arnhem Land. Before any paint can even be applied to the bark, it has to be carefully stripped away from tree trunks after the wet season and flattened over a fire, which undoubtedly requires skill and precision in itself. A common and traditional technique used by artists to create these paintings is known as rarrk, or otherwise referred to as fine cross-hatching. Not only does Mawurndjul have a strong command over this technique but he also employs these traditional motifs in radical ways to express, not unlike Kngwarreye, his spiritual and cultural values. One of his larger pieces, ‘Buluwana’ 2002, is a prime example of Mawurndjul’s technical prowess and relationship with his land and its stories. The Dreaming represented in this painting is that of Buluwana, one of the first people to inhabit the Kurulk clan region at Ngandarrayo. Buluwana and her family were camped here during the time of great drought and were very weak from thirst and close to death. It is at this time that they were confronted by the malignant form of the Death Adder snake that crushed and turned Buluwana into stone upon her attempt to escape. [17] An arrangement of rocks still stands on those grounds as a representation of Buluwana’s present form, where the Ngandarrayo site holds great significance and sacred value to the people of the Kurulk and Kulmarru clans. It is no surprise then that Mawurndjul has chosen to represent, on an immense scale, one of the legends belonging to the Kurulk clan estate, where he lives with his family.[18]

The almost two-meter long, marble-like figure of ‘Buluwana’ is both striking and awe-inspiring at once. The visual distortion and reductive features of Mawurndjul’s ‘Buluwana’ is almost akin to the cubist nudes of Pablo Picasso. The amalgamation of foreground and background, achieved through the merging of Buluwana’s body with the landscape, reduces her form to a mix of dismembered limbs, absorbed in an intricate field of rarrk. The sporadic, yet balanced cross-hatching used in this artwork, dominates the surface and encodes numerous secret meanings.[19] Curator and writer, Hetti Perkins suggests that one of the more “distinctive” features of Mawurndjul’s art is his use of white to offset the otherwise nude-toned colours in ‘Buluwana’.[20] Perkins states that the white pigment used in his artworks is a rather potent material as it “is sourced from a sacred site in Mawurndjul’s Country”[21] i.e. in the feces of Ngalyod (Rainbow Serpent). In this way, Mawurndjul is not only “deftly manipulating the graphic potential of colour, he is also harnessing the sacred energy of Ngalyod in his work.”[22] It is unambiguous that in experimenting with his use of rarrk and the iconic representation of Dreamings related to his kin, Mawurndjul’s artworks are testament to his strong connections to land and ancestral power, where after years of its creation, the story of “Buluwana” continues to live on, almost as an eternal, living entity.

The artworks of Rover Thomas, one of the most influential Aboriginal artists in the history of the East Kimberley art movement, are of empirical significance when considering the concepts of ‘time’ and ‘place’ represented in Indigenous artworks. His art had its beginnings in a visionary dream sequence, which occurred in 1975, after the passing of a classificatory mother.[23] Sometime after her passing, the spirit of the deceased woman revealed to Thomas, her journey across the Kimberley back to her home near Turkey Creek, and endowed him with the songs, ceremony and images for a new Dreaming, referred to as the Krill Krill Dreaming.[24] The responsibility then placed on Thomas to sing his relative’s spirit back to her Country was of utmost importance as the safe return of her spirit, as argued by Dr Stephen Muecke, professor of ethnography, “is imperative to the wellbeing of the place so that it may continue as an enduring life source and again be the site from where life will continue to emerge.”[25] The subsequent artworks that came out of this invented Dreaming, specifically those created by Thomas himself, continue to captivate viewers around the world.

Thomas’s ochre paintings, despite their apparent simplicity, capture the soul of the East Kimberley landscape in both a geographical and spiritual sense. His painting ‘Nilah Marudji’ (Rover’s Country) 1996, like most central and western desert artworks, is characterised by an aerial and almost omnipotent point of view. Thomas’s illustration of his land in this ‘bordered’ artwork, consisting of an earthy-toned landscape outlined by vibrant white dots, draws the viewer in to further engage with these painterly applied and textured ochres. The rich and burnt umber tones of the landscape communicate a deep and lasting connection shared by Thomas and his land, where his landscapes are usually underpinned by a distinct sense of spirituality and mythological significance. The surrounding, stark white dots serve as a means to draw the eye of the viewer along the pathways of the story that Thomas is communicating, following the forms of the landscape, encrypted with key events. These dots create a perfect balance between the earthy landscape and the use of black in the center of the canvas, perhaps suggesting a waterhole. His strategic use of colour and overall image construction works to create an alarming, yet strangely emotional intensity, which unequivocally displays his bond with his Country.

These ideals are corroborated in Australian journalist, Nina Caplan’s article on Aboriginal Australian art, which includes an interview with an Indigenous Queenslander, Den. Caplan states that typically, in Western art, a landscape typifies its subject, whereas in Indigenous art, it is the land that explains the artworks. Her interview with Den enlightened her of the fact that, for Aboriginal people, “everything starts and ends with the land.”[26] The dashes, circles, and fine contours expressed in Indigenous artworks act as a “map and icon and more.”[27] Similarly, the rich and earthy palette, in conjunction with the simplistic yet engaging depiction of “Rover’s Country” mesmerises the viewer as they are presented with an ancient yet timeless landscape. By viewing these artworks in light of the artists’ relationship with their land and their Dreaming, the intensity of the visual is so encapsulating that one no longer questions the temporal aspects of the art. Whether the narrative of the artwork is based on an event that occurred yesterday, or 200 years ago, becomes irrelevant. This is not to say that an understanding of time and its implications on Indigenous culture and artworks is insignificant. However, the very ‘timelessness’ or ‘eternal’ qualities of Indigenous artworks that scholars refer to, as argued above, stems from their connection to ‘place’, and any attempt to adequately engage with Indigenous artworks should avoid analysis solely based on conventional understandings of Indigenous time.

Time and place undeniably hold different values and meanings in different cultures. Indigenous Australian’s perception of time remains a topic of debate, where anthropological understandings of their philosophy of time, albeit perceptive, are not clearly visible in Indigenous artworks. Several arguments can be made as to why there is an apparent lack of a visual representation of time in Indigenous artworks, however, this makes the process of engaging with these artworks quite prohibitive and detracts the viewer away from their optical dynamism. In saying that, the depiction and connection to ‘place’, in Indigenous artworks, is unmistakable. Land can mean a lot of things to different people. To the average Australian, it could mean an asset they can own if they work hard enough. To a farmer, it could be a means of living. To Indigenous people, as explicitly communicated in their artworks, their Country is not something they own, but rather a part of who they are and holds immense spiritual value to their being.

Written by Amanda Brachio

Image: Emily Kame Kngwarreye – Emu Woman 1988–89. Synthetic polymer paint on canvas. 92.0 x 61.0cm

For citation sources, please CLICK HERE