Many of the online definitions for ‘mote’ relate it to a perceptual impediment, a speck of dust in our eyes.

The dynamic nature of perception, constantly reshaping the reception and evaluation of an artist’s creative output, remains an integral concern within contemporary art practice. That our perception changes as contexts change is now commonly understood, what is less commonly known is that our perception is also in a state of constant physiologically change. “Perceptual adaptation” is the term applied to this activity within our sensorium and nothing demonstrates it more clearly than our visual perception of the world.

We see upside down, the images projected onto our eyes’ retinas are upside down. It appears that to make sense of our environment we instinctively and unconsciously develop the capacity to flip this image very early in our formative years. What is clear from research into this phenomenon is that we flip our vision in correlation to our touch of our environments. In effect we feel, rather than see, the right side up.

The three artists in this show privilege us by revealing parts of their lives in which they are perceptually adapting to significant loss, to an erosion of their worlds. While we may not be aware of the direct circumstances they are adapting to, their honesty and courage gives these works a poignancy we respond to. Having discussed these works with them I have glimpsed what has been lost; belonging, relationship and intimacy. How we address loss, how we grieve cannot be reduced to manageable parts. It’s a matter of allowing our selves to feel the new shape of a place after loss has eroded it and adapting. These three artists have scribed their lived experiences of adapting into materials, processes and form.

belonging:

Having refined her material palette in her last body of work Tess Mehonoshen hones and extends her vocabulary of marks and materials in this body of work. With references to wrapping, gathering, tethering and the intimate familiarity that comes from belonging, these bundled foldings give tactile shape to the loss of a rural family home.

The packages are a containment, some spill their folds to reveal their interiors. All are fraying and give off an inevitable residue of dust, even the act of containing effects a loss. From the new material – bitumen – disquieting bundles emerge, a further act of containment and at odds to the transition from raw earth to urban cement. These are almost a dead weight, and yet their presence does not overpower the clear narrative of adaptation. It’s futile to ignore loss, though denial is a fundamental part of its embrace. Naming things is a political act but it is also a release, and the visual naming of these perceptual impediments exemplifies the tangible role art can play in our lived experiences.

relationship:

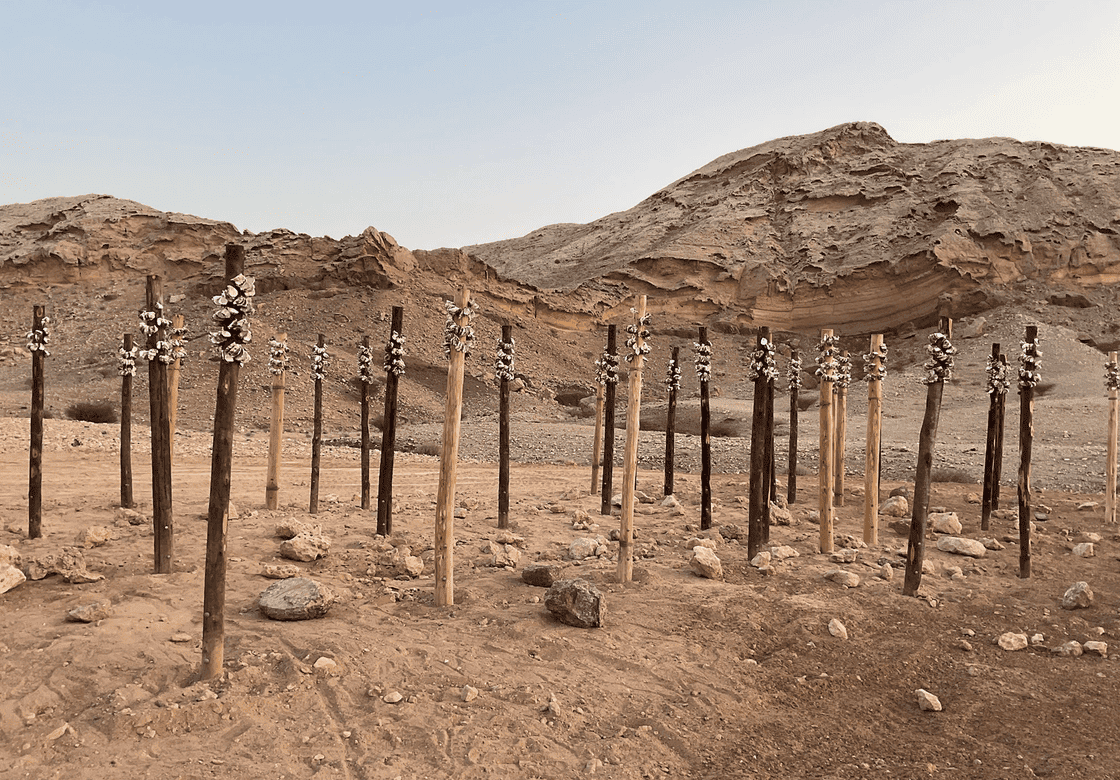

Alison McKay’s work is fragile. Her practice is vulnerable and reflects the nature of her concerns. How do we describe an event when the language we use effectively alters its representation. In these works we are confronted with paradoxes supported by teetering structures. The material forms are tenuous and yet the immaterial here is substantial.

A suspended rectangular sandscape, orderly pierced by nails and eroded at the edges. We sense this object might fall any moment in a number of ways. As in all of McKay’s work there is an insoluble tension in this piece, evident in the relationships between its material parts. Take the escarpment edges, the unstable nature of sand and the piercing nails. Experience would tell us a nail probably formed these edges and yet the ordered rows of nails imply a more resilient substance than we sense.

These works ask us to be quiet, to consider the nature of relationships, of the inevitable loss that must accompany gain, the grief that must accompany love.

intimacy:

Working with materials that replicate a familiarity with our bodies, Naomi O’Reilly asks us to consider, what is it we loose when a visceral intimacy we share with another becomes distant.

Rest comes to mind as I consider O’Reilly’s question. The familiarity I share with my partner of our bodies emphasizes our blemishes. Combined we are a place, we need each other to rest from the incessant voices,

internal and external, that question our appearances. Change is fundamental to intimacy and touch within a relationship is integral to adapting to change. Out of touch is literally a loss of touch and a loss of place.

O’Reilly places us within a tiled space, a surface designed to tolerate the aggressive cleaning agents we are promised will help keep us clean. In a climate of hyper sensitivity to being clean, of touched up colours and images, our familiarity with our bodies is difficult to discuss and O’Reilly successfully engages us.

moat:

As with any language the capacity to express is tempered by the inherent constraints of a vocabulary. A moat might protect us if we cut our selves off, but from what? Language is a two way street, to remain in touch is to remain vulnerable, to separate from touch is to distance, to loose a capacity to perceptually adapt to our changing environments.

Feeling is still the only way to sense the right side up.

Written by Tim Mosely.

From the exhibition ‘Mote’, featuring artists: Alison McKay, Naomi O’Reilly and Tess Mehonoshen. The exhibition was shown at Queensland College of Art – Webb Gallery from the 11th – 28th January. Tim Mosely lectures in the Fine Art program at Queensland College of Art.

Image: Alison McKay, Untitled Sand (2016)