What is it that makes someone a fair dinkum, true blue, Aussie bloke? In Larrikins: A History, Brisbane based historian Melissa Bellanta posits that an understanding of larrikinism ‘unlocks the secret to Australian national Identity’.¹ The publication highlights violence and humour as being key to the construct of the male larrikin.

From the fictional characters of Mad Max and Crocodile Dundy to the hyper-personas of Angry Anderson and Steve ‘The Crocodile Hunter’ Irwin, the images and narratives of white Australian, male icons often reflect Bellanta’s definition of a larrikin, prevalently playing on themes of hyper-masculinity, hierarchy, and humor. Through these iconic characters we glimpse the socially ingrained male disposition toward violence, his insistence on displaying domination over the animal kingdom, and his keenness for comedic action. Such icons undoubtedly play a big part in the construct of the Australian male identity, but there’s something that undermines the logic of their role as representative of the typical bloke. They do emit a typified ‘everyman’ aura, and their feats of excellence portray an ‘everyman can be a hero’ scenario. However, this quality becomes undermined through the recognisability of the famed icon, as it inevitably affords them an elevated status. This iconic status destabilises the hierarchical balance of the everyday Aussie bloke.

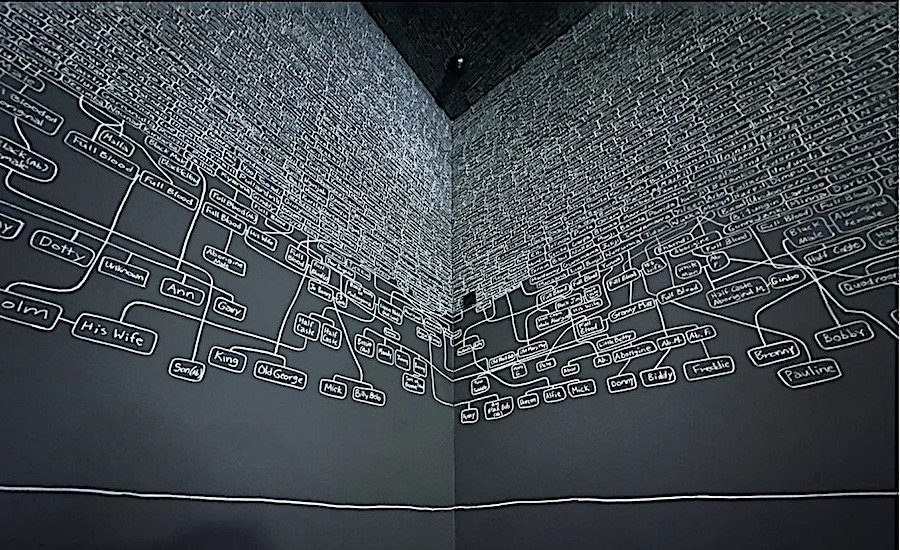

In his exhibition Low Blow, Yannick Blattner presents a body of paintings that investigate the construct that is the Australian male identity. He investigates the themes of hyper-masculinity, hierarchy, and humor, but he avoids the use of celebrity icons, and instead presents anonymous subjects that are more representative of an ‘everyman’ discourse. Not only does Blattner seem to be probing his position as a male, he is simultaneously examining his position as a figurative painter in the context of Australian identity.

By employing a method where a subject’s selection is determined by the highest ranking of search engine results, he hones in on images that are highly democratic in their representation. If Skippy was featured in Blattner’s paintings of kangaroo’s fighting, then one’s reading of the work would be altered. This would also be the case if the paintings featured any of the aforementioned icons above, but the subjects in these paintings are nameless, faceless beings, robbed of their identity in the name of identity. The ubiquitous nature of the rendered subjects alleviates the images from being weighed down by the narrative baggage of a specific icon, while the commonality and clichéd nature of these subjects reinforces the seemingly surface-level guise that Blattner coyly cloaks his allegories. Inevitably this clearing out of narrative noise allows the room to delve deeper into the investigation of a set of more generalized myths and narratives that are at play in national gender constructs.

The works’ references to the national symbol of ‘the boxing kangaroo’ highlight the use of anthropomorphisation, and confront the myth that the image portrays. Given the case of ‘the boxing kangaroo’, the question must be asked; are the attributes being projected unidirectionally? Is it simply anthropomorphism, or are their elements of reverse anthropomorphism at play too? In dressing the kangaroo up in boxing gloves are we displacing hierarchy by simply ‘elevating’ the animal to the status of humanity, or does one simultaneously create a scapegoat that permits a foregoing of humanity, as it ‘lowers’ itself to the primal level?

In a study of kangaroo identities in popular culture, Peta Tait proposes that while “contact with live and representational animals in a familiar setting reinforces habituated patterns”, less familiarized contact can “interrupt these patterns […] to expose underlying beliefs.”² Blattner’s paintings portray men and kangaroos, respectively, in familiar scenarios that are reflective of each other, drawing parallels between the primal behaviour of animals and the belligerence of Australian male. In turn, however, he confronts the destructive acts of these familiarised representations through a creative act; a creative act that is willed to interrupt habituated patterns, and “expose underlying beliefs”.

By Jake Sun

1.Bellanta, M. 2012. Larrikins: A History. University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, p. xi

2.Tait, P. 2014. “Caught: Sentimental, Decorative Kangaroo Identities in Popular Culture” in Boyde, M (ed) Captured: The Animal Within Culture. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, p. 175

Courtesy of Spiro Grace Art Rooms