Despite a proud history, the place of the motorcar in Australia may well be at a turning point. In the current frenetic era of innovative technology and inbuilt obsolescence, many of the items we only dreamt could exist are now often taken for granted, or discarded quickly without a thought. Is the car, formerly an object of prestige, now in danger of becoming a prosaic necessity alongside other items such as flat-screen televisions and air-conditioning? Or, even more extreme, could we ever imagine a world where the humble family car did not exist and our local region was virtually car-free?

Commentators worldwide are reporting that attitudes towards cars are changing; humanities scholar Catherine Simpson predicts that “Sometime this century the one-tonne, privately owned, petrol-driven car will become an artefact…”.[i] This idea is not as futuristic as it may at first appear. Indeed, in one sense the move from the family car to artefact has already begun, and is well accepted in the Moreton Bay region. Here, early model classic cars are a popular love object and the second or third family car may indeed be a classic. Unexpectedly, the family cars of our childhood, the EH Holdens and Ford Falcons, have now become sought-after collectors’ items.

The owners of these classic cars invest time, money, energy and emotion into their upkeep and public presentation. The latter could be the rather informal Sunday afternoon family drive or a more formal presence at the local “Old Skool” or “Show and Shine” meets. At these community events, held regularly in the region, cars, prepared with love, are shown with pride.

The key to these enthusiasts’ love and passion for preserving this culture has been described as the emotion a car can elicit from its owner. Car restoration, care, or maintenance returns us to a time when the car was much more an item of love and desire. These cars not only remain as wonderful artefacts of our past but the enthusiasts unwittingly take on the role of historians of a culture under threat.

Car enthusiasts come in many guises and, in a region where there is considered to be a massive interest in cars, most are represented. As collectors, some focus on the single object of desire, usually a particular brand or model, while others collect en masse, such as one elusive, locally based private collector who has over 100 muscle cars. There are those for whom their classic car is their daily drive and others who drive them infrequently, often in the company of liked-minded collectors. Where some cars are restored and kept as close as possible to their original state, others are enhanced for looks and performance.

However, a drive along Morayfield Road, which stretches from Burpengary to Caboolture, will reveal that the focus is not always early model cars; some enthusiasts modify contemporary cars to provide personalised expressions of appreciation and love. This glamification is most noticeable in the cars of younger drivers as they assert their place in the world and wait for the time when they have the financial security to indulge in more classic motor passions.

With several local car clubs and access to necessary car-based service suppliers, car enthusiasts are well supported across the Moreton Bay region. However, there is also a strong history of car-based activities that has shaped the region’s car culture. According to Steering Column News, the newsletter of the Classic and Historic Automobile Club of Caboolture, “During August 1946, the abandoned World War 2 Strathpine No.2 Airstrip (now Spitfire Avenue) hosted Queensland’s first post-war motor racing. The track was made by Snow Sefton (1911–1991) and fellow enthusiasts by ‘borrowing’ the Pine Rivers Shire Council’s road making machinery.”[ii]

In 1961, car enthusiasts were also responsible for the establishment of the Lakeside International Raceway in the area. The raceway not only gave a home to Queensland drivers such as Dick Johnson but also provided many local car enthusiasts with a taste of racing car culture at the top of its game. The facility continues to support the local car community through open-day events and access to its track.Snow Sefton with the ‘Strathpine Special’ racing car outside his garage (formerly Bagwell’s Garage), Gympie Road, Strathpine, late 1940s. The buildings on the opposite side of the road are located on the site currently occupied by Westfield Strathpine. The ‘Strathpine Special’ was a 1936 Ford V8 powered motor racing car, which was mainly constructed from Ford parts. It was capable of reaching speeds of around 100 mph (160 km/h).

For many, the car facilitates a particular lifestyle and gives them the mobility and freedom revered by motorists throughout history. While in the 1960s, a car was a family’s second-largest investment (after a house), most families today own two or more cars. This is of course, quite understandable: how else could a family facilitate daily trips to work, school, shopping, sporting events and other entertainments? The mobility of the region’s residents has been historically dependent on this mode of transportation and, for over a century, governments have been providing the infrastructure. But what is it about the communities that have grown along the stem of the Bruce Highway as it snakes its way northwards that makes them not just drivers, but a little car crazy?

The Moreton Bay Region reaches from The Hills District in the south to Woodford in the north, and as far west as Mount Glorious, to the shores of Moreton Bay in the east.[iii] The region covers over 2,000 square kilometres and, at 2012, had an estimated resident population of over 400,000 people,[iv] making it one of the fastest growing regional centres in Queensland. Early residents used motorised transportation to facilitate local agricultural industries, but as aerial photographs of the region over time testify, roadways have always held centre stage in the physical make up of these communities. During the 1970s and 1980s, the electrification of the railway line to Brisbane, development of the Bruce Highway to freeway (motorway) standard, and the availability of cheap land contributed to the area’s popularity and a sharp increase in residents. By 1997, population growth had exceeded 30 percent.

As nearly half of its residents commute outside the region to work, the region has developed a “strong car culture”,[v] and it is estimated that “87% of all trips in the Moreton Bay region are made by private car”.[vi] This situation is not unique to Moreton Bay residents. During the twentieth century, the automobile became the most dominant form of movement throughout the world. However, as mentioned in the introduction, this may change in the not-too-distant future, with improved public transport facilities and an increased awareness on environmentally friendly practices.

Nevertheless, the motorcar has continued to captivate us since the late-nineteenth century, when models capable of carrying people first appeared. There are ongoing discussions surrounding its position as an item of love or ambivalence; significance or insignificance; practicality or pride. Sociologist John Urry hypothesises that the motorcar industry spawned an “entire culture” that has “re-defined movement in the contemporary world”.[vii] It remains an integral part of contemporary Australian life and, although the potency of its influence has varied over time, many communities and their local culture – such as those that comprise the Moreton Bay region – have been heavily shaped by the presence of the motorcar.

Written by Elizabeth Bates

Endnotes

[i] Catherine Simpson, “Cars, Climates and Subjectivity: Car Sharing and Resisting Hegemonic Automobile Culture?” M/C Journal 12, no. 4 (2009), http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/viewArticle/176.

[ii] Classic and Historic Automobile Club of Caboolture, Steering Column News, September 2005, 6.

[iii] Moreton Bay Regional Council, MBRC Draft Travel Demand Management Strategy 2014–2031, March 2014, 13, https://www.moretonbay.qld.gov.au/uploadedFiles/common/publications/Travel-Demand-Management-Strategy.pdf.

[iv] Australian Bureau of Statistics, cited in ibid.

[v] MBRC Draft Travel Demand Management Strategy, 6.

[vi] Ibid., 17.

[vii] John Urry, cited in Simpson, “Cars, Climates and Subjectivity”.

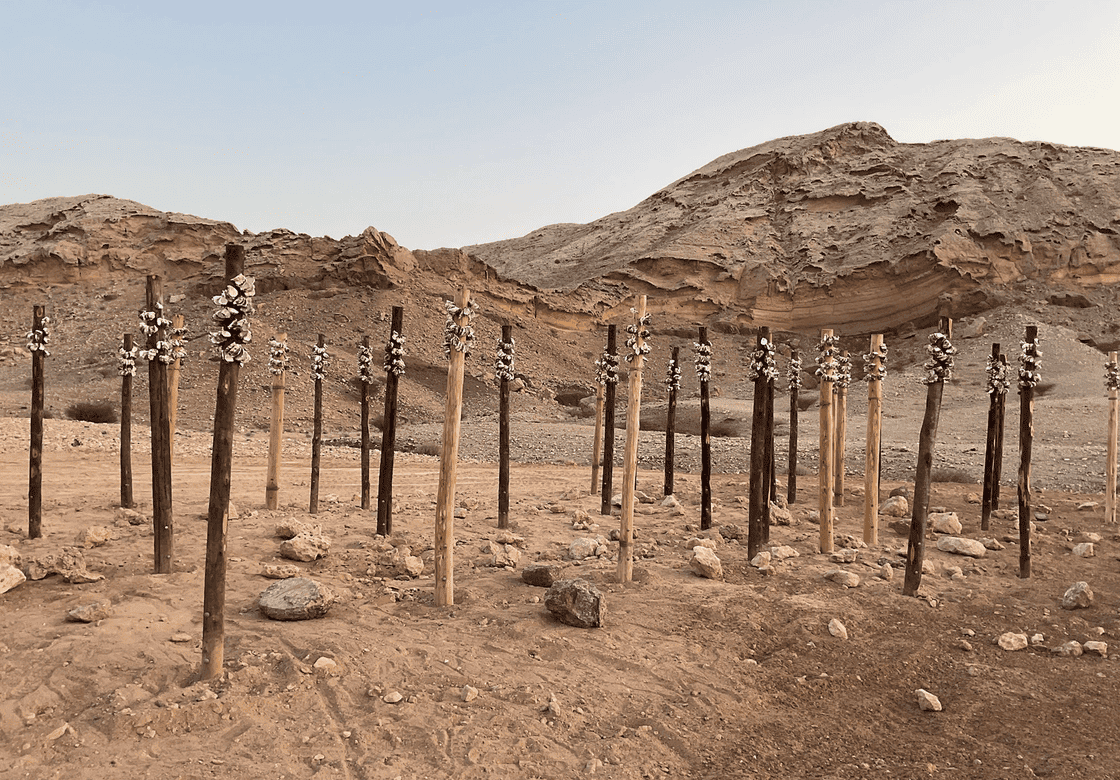

Image: Daniel Wallwork, Rev – the Cult of Mount Panorama 2006, Installation detail.

Exhibition: Cars: My Automolove at Caboolture Regional Art Gallery