In a city weeks after the snow filthy chunks of ice remain in the streets, in gutters and on freeway verges. Cars that have been parked for a number of months drive away leaving holes in the ice. There’s a desperate feeling of weight, the simultaneous heaviness and lightness of opening a large stone door and finding it light as plywood; of taking the last step and finding none there.

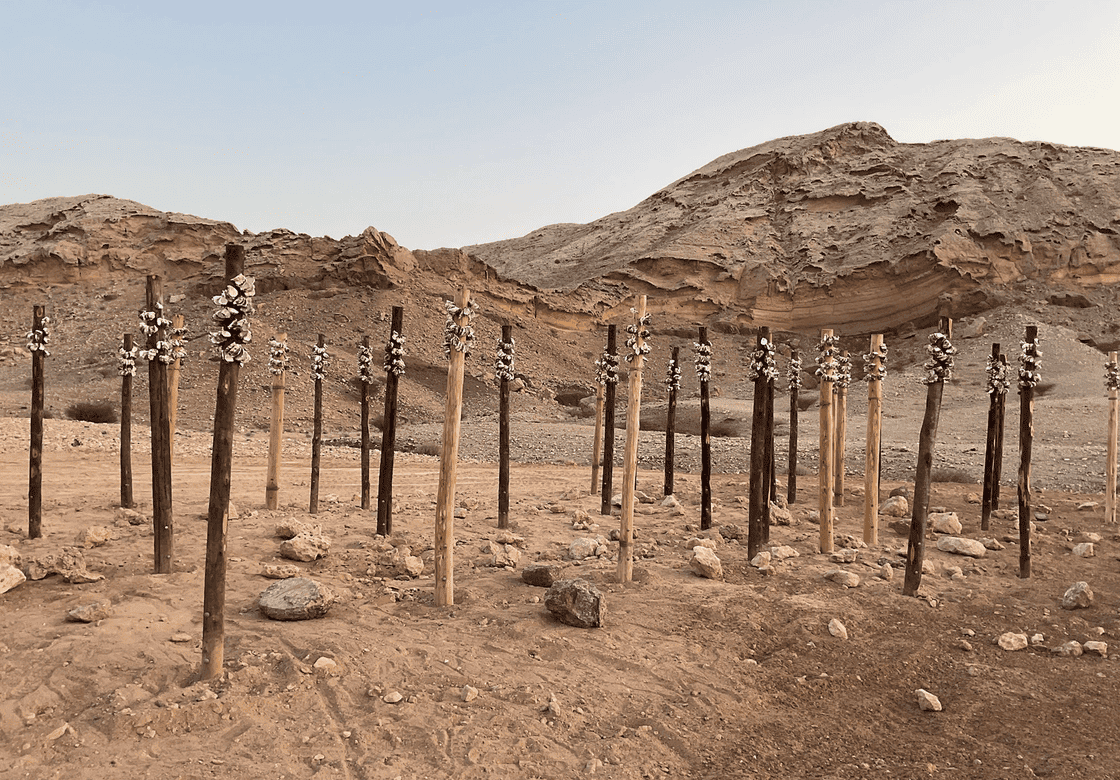

The sculptures that make up Charles Robb’s Loss Control II summon something of this same strangeness – an awareness of one’s own body and the objects that make up our surroundings.

Conceived as a continuation of Robb’s ongoing investigation into self-portraiture and cast in a muted palette of greys and ivory, the works are arranged in a series of tableaux conveying the ‘strange slippages’ between conscious and incidental forms: the hidden order of the world.

In this collection there are two self-portraits. Two loose heads. Both shrouded by something, features partly obscured, and fashioned in matte off-white. In Pleurant, slightly miniaturised, a man with cloth pulled over his eyes is both sad – the weeping figure – and a little menacing. There is a senseagain of the hyperawareness of having a body, of the weight of a body, of anxiety and uncertainty. Which way from here.The world feels temporary and loosely tied together. Self-portraits may be the oldest and yet most contemporary thing: simply looking at yourself. Looking at yourself for so long that the image quits and you are just pixels or pieces of dust caught by the light. Looking at yourself until hair sprouts from nose and ears and chin and eventually hides your features entirely.

This is the story implicit in the other figurative work, titled Primitive Accumulation, where something like a forgotten bust of Neptune lies sideways on a plinth overgrown with hair, marking an equivalence between the movements of the body and the movements of nature: growth, decay, and stasis.

Around the back of the museum at Pompeii they keep some of the bodies – less perfect specimens, perhaps, or simply spares – stored frozen in their dying pose. They lie horizontal, placed roughly in dusty vitrines like too-large fish in the bottom of an abandoned tank. The queasiness of this mute statuary, left behind in a kind of tool shed, announces a sublime anxiousness that is also present in these works.

Self-portraiture acts as an acknowledgement of the quiet chaos of the world, of the un-monumental and the extraordinary quality of dailiness. In this hierarchy the head is a subject or – and – an object, eyes obscured or staring into some other plane. Robb’s textured surfaces suggest the lumpy interior of a country or the surface of a body, soft and hard and slow.

The most visual link between the objects and their provenance in the studio is the dim colour scheme throughout. A palette of neutrals like this means storminess, winter, a pale cool hand dipped into bathwater, a wax candle lit warm from the inside. They are colours not really colours but the suggestion of colours, muted greyish and cream and mink and dirt, like a city from far away, like weather, like dust, like pale ocean. Flesh is matte and creamy, hair still when wrought in stone. Dryness.Bodies turning to ash.Weather feels like a constant presence in these works, bright terrible windy days when the sky is highest and everything is cruel, when it’s blustery and a tepid breeze is blowing hair into your mouth.

The casting process carries with it another set of meanings, in this case the dance of authenticity occurring between objects modelled, found, or collected from ephemera in the studio. When casting in multiples you lose the idea of an original – and when casting from life one realizes that the original can no longer be there.

In an interview, Robb told me: ‘When you’re modelling something like your own head, there is a precise surface that’s either right or wrong – and a slight margin for error. What I loved about modelling the rocks, and making an artificial rock, is that you’re on this quest for something authentic and also perverse, trying to model this thing in such a way that it looks completely undifferentiated, it looks like it’s something that’s just a lump by a roadside. And you realize that you have to approach the problem completely differently as a sculptor.’

There is certainly something luminous and funny in the act ofbuilding a stone. Stonesfunctionas a transportable fragment of place, for they carry the place that they’re from and this memory cannot be erased. Maybe in the presence of another we are endlesslypocketing their mannerisms for a quieter time, when they can be turned over in the palm like lit stones.

The low pedestals holding each tableau have a quality of precarity, of

spindliness. The balance of stones on hillsides kept in place by faith. This unsteadiness mimics Robb’s twinned investigation into the two orders of objects – harmonious and chaotic, elegant and pathetic, light and heavy, the singular and the multiple. Art is a transfer of belief, of feeling, and in these indigestible interior vistas Robb combines rock formations and relics with a grey half-thought, things on the verge of falling but not yet.

This shakiness combined with the perfection of the forms creates another binary in the presentation, marking an equivalence between stones and bodies that seems related to weight and drowning. Lumps – bitumen – poured concrete, flesh, plaster. Here limbs and heads are equated to boughs and stones, always shrouded or somehow melting.

The experience of these works contains endless pleasure: all ancient ambience and bodily memory,the casual vulnerability of objects and of bodies in landscape, introspection and contemplation. But they cannot escape the idling horror of being alive, or the realization that all we have in the end is a corpse and the colour of the weather.

Written by Madeleine Stack

Image: Charles Robb, Loss Controll II (Exhibition Installation). Photo by Carl Warner

Courtesy of Spiro Grace Art Rooms