Folds of Belonging, curated by Tess Maunder, is an exhibition of lightbox images in Brisbane’s CBD. It runs concurrently with the BrisAsia Festival (27th January – 19th February, 2017), and features works by both emerging and established artists from Asia: Fahd Burki (Pakistan), Motoyuki Daifu (Japan), Rirkrit Tiravanija (Thailand/USA), Shilpa Gupta (India), and Slavs and Tatars (Eurasia). Maunder has curated an exhibition that investigates the terms on which diasporic cultural groups from Asia find a place in the social fabric of Brisbane. The artworks in Folds instigate exercises in social connection and cultural inclusivity in order to nurture a sense of belonging within the Western city.

The exhibition is hence founded on visual cross-cultural communication. The works of culturally disparate artists engage in a dialogue with diverse public audiences. By acknowledging the cross-cultural nature of the exhibition, belonging in Folds can be predicated on the acknowledgment and appreciation of cultural difference. Belonging is precisely to not just feel a part of a larger whole such as the city, or to acknowledge the many similarities between different communities within Brisbane’s community. Belonging is the act of acknowledging the self as existing alongside other cultures and selves while inhabiting the homogenous cityscape. It is necessary to ask what kind of belonging is argued for by the exhibition, and whether it is equitable within the power dynamics of the Western culture of Australia.

In Eagle Lane, a diptych depicting a single Shilpa Gupta photograph is placed near a triptych by Rirkrit Tiravanija. Gupta’s Untitled Don’t See Don’t Hear Don’t Speak, 2006, depicts four children acting out the proverb “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” They are arranged in a tiered formation, rising into the background of the photograph. Each child covers the eyes, ears, or mouth of another, except the girl at the front.

The children appear sombre, any playfulness connoted by the proverbial game undercut by their firm hands and sideways glances. The tension and determination contained on the face of the young boy on the photograph’s left-hand side reverberates throughout the image as its only unobstructed facial expression. It is a focal point and a key to interpreting the body language of those around him.

There is a physical connection between the participants accomplished through the intruding hands. The children are corporeally linked, a haptic connection with one another accomplished by incapacitating acts. Linkage is hence founded on the disabling of a sense. Disconnection underlies connection. The children are unable to equitably engage with those they are connected to, and at the same handicap one another.

The work questions on what terms connection takes place. It does not belong in Folds because it stops short of representing or creating a sense of belonging. Gupta problematises the idea of interconnectivity. If belonging is founded on a connection between different individuals and cultural groups, then it is necessary to ask what kind of connections are taking place. Untitled invites the viewer to critique the way interpersonal and cross-cultural connections are advocated for by the works in Folds. The type of connection defines the sense of belonging, how power is transmitted between different entities, and if cross-cultural engagement is equitable. This probing then of course makes it a part of the exhibition, an antithesis within the dialectic of Folds.

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s triptych untitled 2016 (folds of belonging, do we dream under the same sky), 2016, is the reimagining of one of the artist’s earlier works.[1] With three lightboxes, he represents the eponymous question in English, Vietnamese, and Chinese Mandarin. The latter two languages are the two most spoken in Brisbane outside English.[2]

Tiravanija’s work, and not just its title, is emblematic of the exhibition’s aim to foster a sense of belonging amongst different cultural groups. The artist asks a simple and immediately answerable question: “Yes, we do dream under the same sky.” And as a question rather than a statement, the work is not an assertion of inclusivity but an invitation to formulate cross-cultural connections. In answering the question, the beholders engage with the points of difference represented by the three languages. Although they may only reply in one of the languages, viewers are responding to all three of the panels at once. They establish a linguistic connection with disparate cultures. Though, this is only a partial connection. Many viewers of the work will only be able to respond in a single language.

A sense of belonging, an equitable coexistence, amongst multiple cultures is established by the willingness of the work to engage with them on their own terms in their languages. Do we dream treats cultures and languages as equals. Although the physical space in which Tiravanija’s work exists, Brisbane city, is one in which English is the dominant language, he short circuits this dominance by representing each language as an equal component of the work.

But do we dream takes as its basis something so broad, the atmospheric phenomenon of the sky, that the resulting connectedness is too general. It does not allow for a meaningful or productive linkage between communities. An expanded answer to the question could be “Yes, we do dream under the same sky. So what?” Invoking the whimsical concepts of dreams and the sky aestheticises this generalisation, but does not define the precise process through which to foster belonging. As Gupta’s work established, connections are fraught and complex, and Tiravanija’s work only partly accomplishes a meaningful sense of cross-cultural belonging.

The next closest work is Fahd Burki’s Hyperreal, 2016, in Hutton Lane. A newly commissioned work, it is a collection of eight lightboxes of varying dimensions representing abstract images. Burki here toys with geometric forms and constructs regimental cross-sections of colour. The images appear pixelated and blurry, replicating the look of an extremely zoomed in section of a picture or an out of focus photograph. Each band of colour is defined by a light central section which gradates into gradually darker tones toward its boundaries. Some lightboxes play off their physical connectedness. The image second from right duplicates the path of the power chord that links it to its neighbouring pictures.

Like any abstract work, Hyperreal instigates a process of diverse meaning creation. The work invites various readings, yet at the same time the viewer cannot decide which one seems more correct.[3] It could be read allegorically, literally, or as an abstract artwork that comments on the similarly abstract cityscape.

As a newly commissioned piece, Burki’s work was created with the space of a Western city in mind. Simultaneously, it is informed by Burki’s artistic education in both Pakistan and London.[4] To look at this work is to be invited into a dialogue with not only Western concepts of modernism, but concurrent Pakistani and South-Asian ones too. The work does not define, reduce, or simplify what constitutes these latter traditions. It acts as a gateway to multiple, culturally contingent readings alongside the various pre-existing readings of abstraction grounded in Western aesthetics. Hyperreal engages with two artistic traditions at once, and advocates for a belonging which embraces duality, fluidity, and the unknown.

The nearby King George Square Carpark houses Motoyuki Daifu’s Still Life series, 2013. The installation comprises eight lightboxes which sit at eye height and follow the downward slant of an access ramp. The photographs are close-ups of Daifu’s kitchen table, depicting the cacophony of objects which populate it. Predominantly littered with food stuffs, the table is also inhabited by a box of band-aids, a gnome, and a miscellany of other household items. Daifu’s bustling photographs do not have a central focal point, as each item has equal weight in the framed chaos. The viewer’s eye endlessly darts around the images.

Still Life references the visual language of advertising, depicting glossy products and bold brand names (some of which will remain unknown and untranslated to certain audiences). But the product that is meant to be advertised is unknown. There are so many in each photograph that not one could be said to be the focus of the advertisement.

In taking food and the kitchen as his launching pad, and representing foods such as sushi and instant noodles, Daifu depicts one of the most familiar forms of cultural engagement relevant to city life. As a part of hubs such as Chinatown or the food markets of the BrisAsia festival, restaurants specialising in Asian cuisine are familiar to many inhabitants of Brisbane. Daifu points to how food is often the medium through which cultures interact. Eating sushi or curry is an accepted part of contemporary life and belongs within Brisbane’s social fabric. Daifu’s pseudo-advertisements of food encourage the visual and then actual consumption of the goods he represents.

But Daifu does not just stop at this acknowledgement of diversity. The untranslatable words and brands on some of these items create a point of difference within the photographs. The content and ingredients of many products are unknown. The artist challenges the viewer to go past a superficial consumption of non-Western foods and delve into the cultural unknown.

By representing unfamiliar cuisine alongside the familiar, Still Life allows the viewer to realise that the two poles are actually quite similar. Many non-Western foods and cuisines have a place of belonging in the contemporary city. They are familiar and accepted. They would have once been startlingly new, an untranslated and unfamiliar cultural product. Representing both side-by-side, Daifu asks the viewer to acknowledge how engaging with the unknown is the first step in crafting a sense of belonging with different cultures.

The final work in Folds, Slavs and Tartars’ ööööpS, 2016, is installed in Southbank’s Fish Lane. Across six identical lightboxes, this collaborative Eurasian group have installed the term “ööööpS” (each letter receives a lightbox). The sharp edges of the rectangular diaereses which sit above the rounded form of the letter “o” differentiates the two from one another. This visual contrast accentuates the linguistic strangeness of the diaereses if the work is read in English as “oops!” This installation is actually a misspelling of the Turkish word for kiss.

Even when the Turkish translation is understood, the English reading of the word is never lost. And once the Turkish misspelling is known, it cannot be forgotten either. Both the English, Turkish, and the misspelling, oooops, kiss, and ööööpS, are all present at the same time. There are multiple understandings of the work understood through the same visual cue (an interesting contrast with Tiravanija’s work arises here). So yes, the work invites a reading of the curatorial rationale of belonging because both Turkish and English are folded into the misspelling as part of the work’s aesthetic texture. Visual and linguistic difference cyclically appears, disappears, and reappears, as the audience engages in a process of translation and cultural education.

All of the works in Folds act as small pinpricks of visual independence within the overwhelming sameness of the cityscape. By aesthetically differentiating themselves from Brisbane’s urban landscape, they advocate for a sense of belonging that allows for diasporic cultures to maintain their independence within a Western city. Gupta opens the show as an artist critical of connectivity. Tiravanija invites cultures together linguistically. Burki expands on how visual art can belong to multiple, culturally ingrained readings. Daifu’s Still Life Series demonstrates how the process of belonging takes place. Slavs and Tartars explores how the differences between languages allow for a playful form of connection. By autonomously arguing for cultural inclusivity, the works fulfil the message of belonging argued for by both themselves and the exhibition at large.

Written by Simon Brigden

[1] “DO WE DREAM UNDER THE SAME SKY,” e-flux, last modified June 12 2015, http://www.e-flux.com/announcements/29383/do-we-dream-under-the-same-sky.

[2] “Greater Brisbane: Language Spoken at Home,” .id, accessed February 11 2017, http://profile.id.com.au

/australia/language?WebID=270.

[3] Also see Rex Butler, An Uncertain Smile: Australian Art in the ‘90s (Woolloomooloo, NSW: Artspace, 1996).

[4] “Fahd Burki – Biography,” Greynoise, accessed February 11 2017, http://www.greynoise.org/Biography.aspx?AID=1.

Essay written for the exhibition ‘Folds of Belonging’ – The Brisbane City Council’s Vibrant Laneways program across sites in Brisbane’s CBD. 27th January – 1st May 2017.

Tess Maunder is an India-based curator and researcher. She was a curatorial collegiate of the 11th Shanghai Biennale and has previously worked at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane. Recently, she and Brisbane Art Guide writer Simon Brigden sat down to discuss her current exhibition Folds of Belonging (January 27th – May 1sst, 2017). Maunder and Brigden here discuss how chance, notions of city-life, and diaspora feed into the show, as well as covering Maunder’s work with the New Delhi based collaborative group Raqs Media Collective.

Click to listen to the – Interview

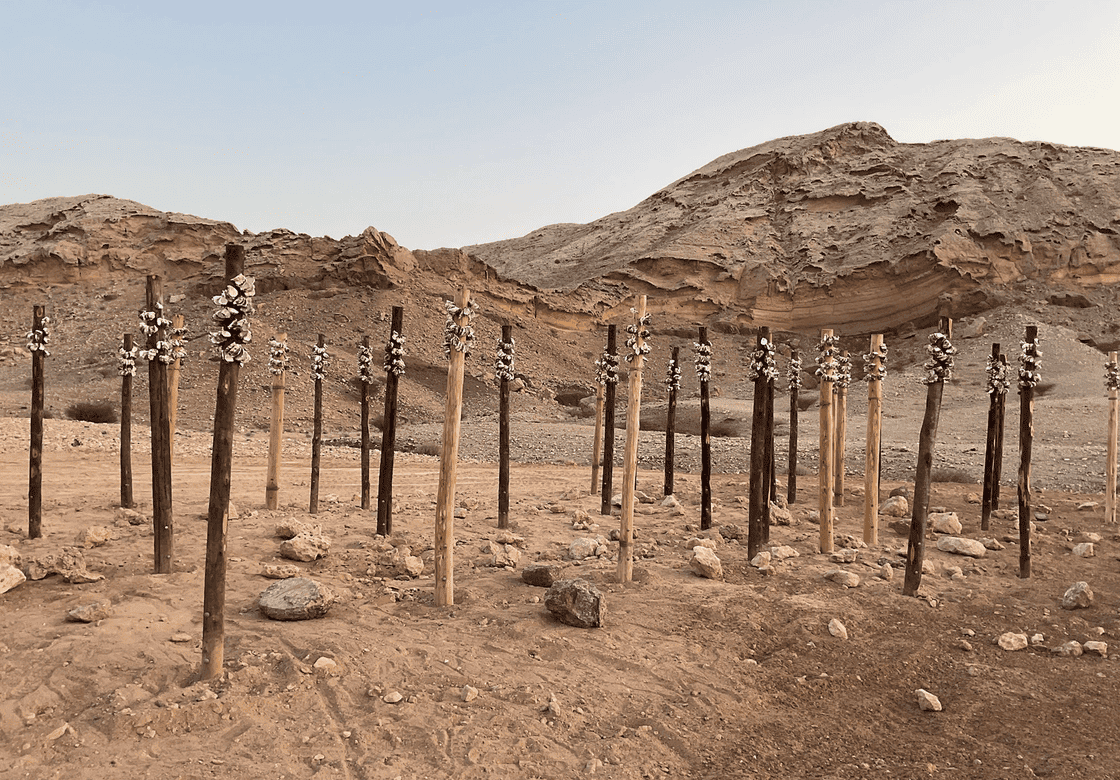

Image: untitled 2016 (folds of belonging, do we dream under the same sky), (2016), digital print, size variable. Courtesy of the artist, © Rirkrit Tiravanija. Photos by Carl Warner