Fiona Foley has had significant success. Ever since her beginnings with Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Ko-operative in Sydney in the early 1980s, her stature has increased – as an Australian artist with national and international standing. A major survey exhibition, Fiona Foley: Forbidden, toured Sydney and Brisbane (2009-2010), noting her influential voice and the breadth of her work. This year she is the recipient of an Australia Council Visual Arts Award, further acknowledging her contribution. She is a regular keynote speaker at conferences and symposia all over the world, and is convenor and curator of Courting Blakness: Recalibrating Knowledge in the Sandstone University (2014) at the University of Queensland, where she is currently Adjunct Professor.

Exhibitions of her work are seen regularly in Australia and overseas. Her second artist video, Vexed (2013), was launched as part of the invitation only University of Queensland National Artists’ Self Portrait Prize (2013) and was also part of EcoCentrix: Indigenous Arts, Sustainable Acts, Southbank London (2013). An integral part of her practice includes art in public spaces.

What becomes evident over a career that spans 30 years is that in every opportunity granted to Foley she uses her art and her public statements to reflect the hidden histories of Australia’s Indigenous peoples, and to seek due recognition for their losses – of people, lands, and life. The tensions that exist within the concept of Australian nationhood are her driving force.

Yet Fiona Foley: Courage offers audiences an opportunity to see Foley in a more holistic and personal light. While she has never hidden from the issues she has faced – as a woman, Indigenous, and an artist now working independently (without the comfort of a collective) – it is the courage within her art practice that is highlighted in this selection of work.

The exhibition notes her exposé of dispossessed Indigenous voices. While it includes artwork from 1994 to the present, it also features objects from her personal collection that relate to the family history that is central to her life’s work. Also included are the tools of her trade – her paint basket and sketchbook – that shed light on her process.

The Legends of Mooney Jarl is a children’s book that narrates and illustrates Badtjala stories. Published in 1964 by Jacaranda Press, it was written by Foley’s great uncle Wilfe Reeves and her great aunt Olga Miller (Wandi) who were siblings. Foley loved poring over these pages as a child, and said, “Uncle Wilfe knew the legends from his father, my great grandfather, Fred Wondunna. I knew it was rare – most Aboriginal people did not have stories published. I felt lucky, culturally enriched really, to have that object in our home and our stories of Fraser Island recorded.”

Another of Foley’s personal touchstones is the Badtjala Dictionary (1996) collated and researched by her mother Shirley Foley. She said, “The precedent of The Legends of Mooney Jarl allowed us to conceive of writing our own history.” Shirley Foley was a strong advocate for the Badtjala people and secured land on Fraser Island for Badtjala use from January 1990. She was a pivotal influence who encouraged Fiona to read widely, and examine material from a broad base. From the first she ensured that Fiona and her siblings were proud of their Aboriginality.

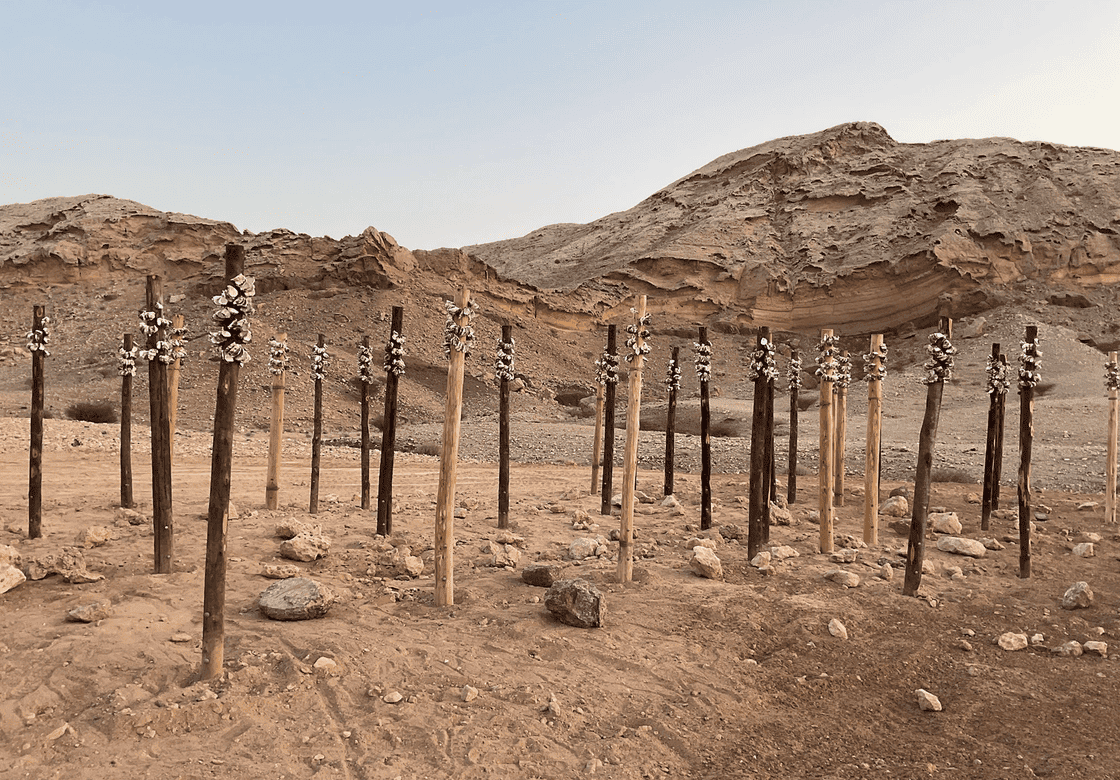

Artist’s proofs of sculptures such as Opium Poppies (2008) which relates thematically to the major public artwork overlooking the State Library of Queensland, Black Opium (2006), and Sacred Lotus Lily (2012), similarly influenced by Witnessing to Silence, 2005 (Brisbane Magistrates Court) mark important historical events in Queensland. Early paintings include Red Ochre Me (1998), and Postcards from Ramingining (1995). These trace Foley’s journey into redressing the wrongs for Indigenous Australians. The latter series is a reminder of Foley’s early visits to regional Aboriginal communities. She says, “Before that, in some ways, I had romantic ideas of what traditional Aboriginal communities and traditional people were like…This helped me realise that I had a choice too, that I could make a difference.” These objects allow us to experience her courage as an artist but also as an individual. The earliest work, Badtjala Woman (1994), refers to an early anthropological image, yet sees Foley herself recast in that anonymous role. The shell necklace and averted gaze are borrowed from the archival image yet Foley defies its objectification, “with an unspoken eloquence of spunk”.

Plein air watercolours of natural elements – mangroves, leaves, shells – made in her country on Fraser Island over May 2011, are simple yet delicately rendered. This was a tough year; the watercolours are tender memories of plants and creatures that exist in a fragile ecosystem. Sea of Love #2 (2007) is a semi-autobiographical outing that traces her experience for art. In its dalliance with the online dating realm, it delves into gender and personal politics.

Bodhi Leaves (Samsara series) (2010) gently evokes peace while noting the similarities between the Buddhist sensibility and the Aboriginal understanding of the sacrosanct environment. Foley’s two artist films are included – Vexed and the evocative Bliss (2008) with its images of poppy flowers. The benign beauty expressed in Bliss speaks to the sinister historical undercurrent of opium use in Queensland.

This exhibition traces the contribution and humanity of a Queensland based artist of international significance. Curator Andrew Gill has made a point of stripping away the usual labels to mark her as Fiona Foley – artist. Yet the exhibition builds a holistic picture of Foley – as woman, partner, friend, daughter and sister – an individual who speaks her truth.

Written by Louise Martin-Chew