Snatches of conversation and the sounds of cars are rising from the street to be funneled into this space. Passersby may look up and see—through the second floor window that Marnie Edmiston’s exhibition A Plant is a Plant hinges on—the unusual sight of a black, imposing parabolic dish staring down at them. It looks comically like a panoptic eye, but it is an ear. If the passersby are speaking, it will take in their words. Though its back is turned to us—the viewers made privy to its workings—it still proffers that we listen in.

Some five metres behind it and well below knee height, two white ceramic receivers perch on plinths that are neatly covered with a bright blue layer of material. The plinths themselves are at an awkward distance from one another—a touch too far for a viewer to stand in the middle and reach for both receivers at once. They are placed on a rectangle of black carpet that is angled diagonally: it faces neither the window where the dish hulks, nor the gallery wall where a curious series of perspectival drawings hang. There seems something ritualistic about the set-up, and it appears at once highly technical and makeshift. A functional hideout, perhaps, that could be dismantled at short notice. It prompts one to ask: what kind of set-up is this? Are we being set-up?

The ceramic receivers share the organic form of a sweet potato sliced clean in half, hollowed out, and glazed. Both are pierced at the top with red cord that is tousled across the room and joined to an amplifier, transmitting through it the sound absorbed by the big black dish. Reach down and pick one up, press its hollow to your ear, and catch what you will. Maybe you’ll hear an argument between lovers, the murmurings of a protest movement, or the conspiring of something criminal, but probably not. What converges is up to chance. Good composition is a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

The perspectival drawings, of which there are six mounted flat onto cardboard, hang around the room on gold hooks that make them appear both delicately levitating off the wall and easily removable. They each reconstruct, on a single plane, a different room rendered through a host of mathematically precise draughting techniques. Inset in each is a photograph that attests to the existence of their referents as real spaces, providing glimpses into living rooms that are obscured by the leaves of a plant or perhaps, as all the leaves look suspiciously similar, a fake plant. Each of these self-consciously covertly taken photographs has been meticulously mapped onto a diagram that reveals the vantage point from which it was taken. They expose utterly neutral spaces—no action, no life, no secrets—but built into their shrouded apparatus is the clear and paranoid expectation that someone could enter the frame of observation at any moment.

The declared banality of depicted content similarly finds form in a vertical row of laser engraved black squares—also hanging from gold hooks—that each bears an almost didactic diagram of an ordinary object. These icons include among them a potted plant, a chair, and a bookshelf. In light of the conspicuously looming parabolic dish, we begin to see these objects as potential, unsuspecting proxies for household or workplace spyware. They begin to beg the question: what are we looking for?

Edmiston’s works, beautifully constructed as they are, still strike us as indiscriminating in all of their specificity. Like the algorithms that harvest and sift through big data, they gather and present a mechanical cutout—a survey sample extracted from the endless fabric continuum of living. What they decisively do not account for is what cannot be mapped; the dimension of life that would vitalise these scenes is the excess that escapes them. These works articulate the ubiquitous paranoia immanent to data collection that, in its exhaustive efforts, somehow misses the point: what eludes them will continue to elude them. The bigger the sample, the more boring the outcome.

Yet the amateurish staged secrecy of the fake plant that frames each of the photographs suggests something else is at play—a conspicuous spy with the desire to be caught. This recalls another kind of spying: that of the female voyeur tracing intimate spaces, as in the seductive game that plays out in Sophie Calle’s Suite Vénitienne, where the artist follows a fresh acquaintance to Venice, setting up camp near his hotel, donning a wig, and recording his movements. In Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie, the filmmaker plants her camera in plain sight, recording scenes of her mother (in her home and on Skype) who repeatedly asks, “Why are you filming me?” In the amusing idiosyncrasies of this hideout, Edmiston’s exhibition notionally restores to the mechanics of technological spying something more simply intersubjective. After all, is a plant just a plant, or is it a plant? Who planted it?

Written by Ella Cattach

Essay from the exhibition by Marnie Edmiston, titled ‘A Plant Is A Plant’ (August, 2016). Courtesy of Fake estate ARI

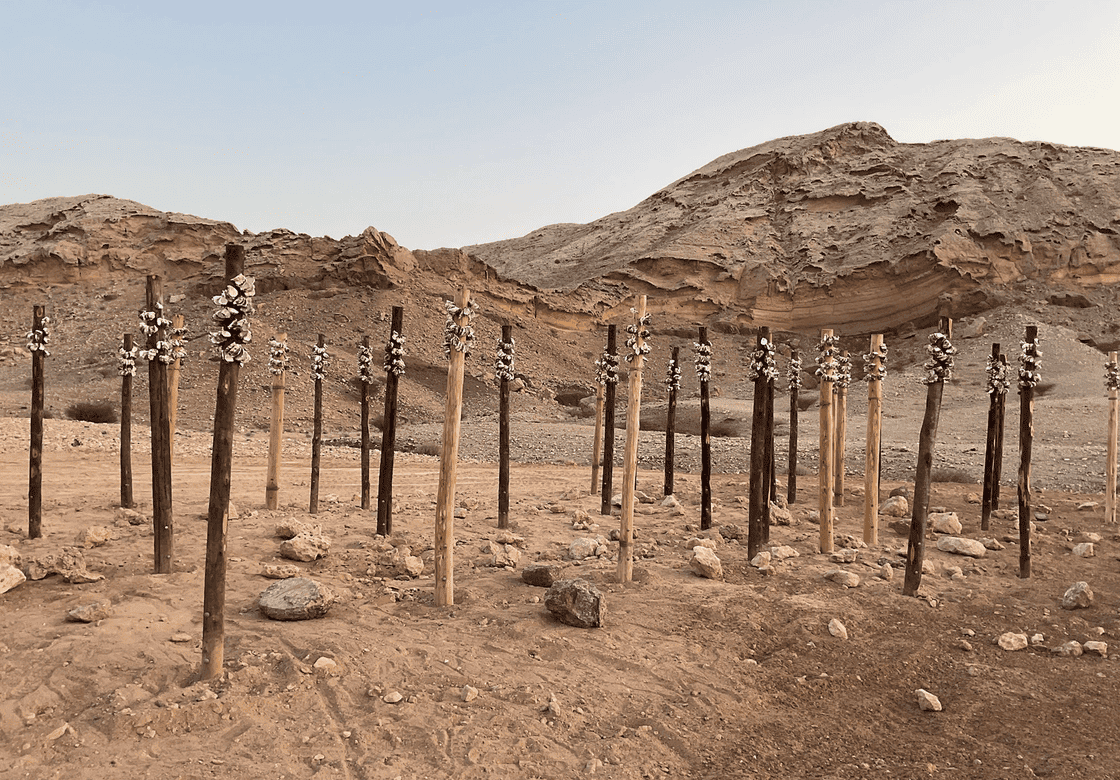

Image: Marnie Edmiston, a plant is a plant, 2016 (installation documentation).