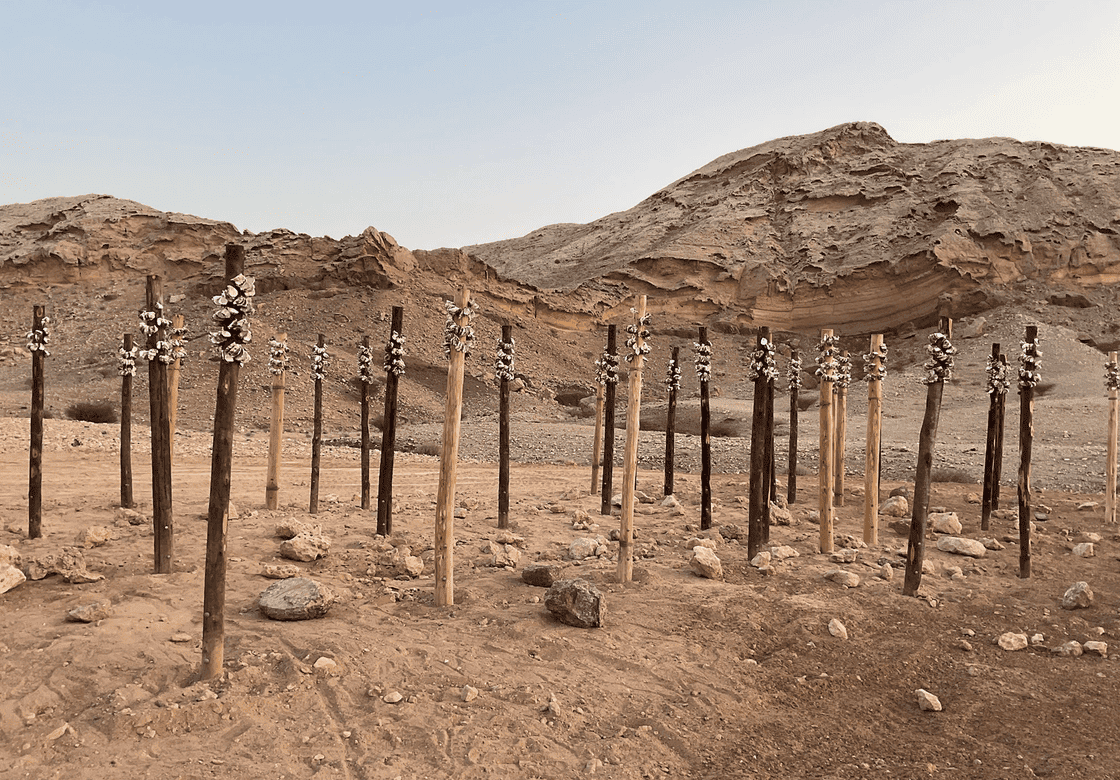

IS ART NATURAL?

The question concerning Art’s relation to Nature is one central to Aesthetics and is bound up with associated problems regarding subject formation, differentiation and freedom. Via F.W.J. Schelling’s 1807 lecture On The Relation of the Plastic Arts to Nature, the task here is to attempt a conceptual illumination of this question that may sit alongside and communicate with Amy Commins’ 2016 light installation LANDSHAPES.

Schelling maintains that the artist must withdraw from Nature, in order to regain Nature with a thousandfold times interest. We can thus say Art partakes in Nature, without presenting Art as coming after Nature in time or sharing an eternal identity with Nature. The common sense platitude, “We humans are natural; therefore our Art is natural” has all but lost meaning for us today. We must vigorously defend the distinction between human compositions (=Art) and non-human compositions (=aesthetic) such as those of the bowerbird, the maple tree, or the horizon at sunset, no matter how prototypical these latter may at first appear. The dividing line is made manifest by the active component of reasoning in sapience and the conscious Idea that nevertheless depend upon and originate in Nature’s unconscious production of aesthetic forms. Those who claim to reside wholly within Nature birth simple incidents of sense-data or ‘larvae’ with a blind purposiveness. In so doing, they naively seek to re-present the actual whilst failing to acknowledge the always already conceptually mediated nature of artistic creation.

Is Art’s relation to Nature parasitical? When Schelling says that Art withdraws from Nature, this is not in an extracting or objectifying sense. Above we said that Art shares no identity with Nature, but this is only partially the case. For Schelling, the artist holds a privileged relation to nature, one inaccessible to the philosopher amongst others. As the creator and wielder of concepts, the philosopher dwells principally in the realm of Thought. They may conceptualise Nature, but such conceptions remain some among many and fail to capture the silent aesthetic dimension of Nature’s forms. Conversely, it is the ability to bring together and put forth both the Idea of Nature and the Form of Nature at once and in one work that gives the artist primordial access to Nature.

Schelling does not mean for his concept of Nature to be synonymous with the Real or the Actual. Denouncing those who see Nature as something static or dead, Schelling views Nature as a productive process in continual mutation. If Nature is a process, then it’s meaning for us can never be fixed; it is an updating and updatable force – ‘For Nature never repeats herself’. Art’s relation to Nature is thus figured as a revealing. Art is able to reveal the Truth or Idea of Nature not by representing instances of Nature A=A (as in the Romantics’ landscape paintings), but by instead representing the creative energy constitutive of Nature. To ‘imitate’ Nature is to separate off and unjustly kill Nature by capturing it as inert and in turn producing the semblance of ‘spectres’. On the other hand, to actively participate in and diagram Nature’s processes is the highest aim of Art.

Given this crucial relationship, Art-making itself becomes revealed as an updatable practice, which via its different modalities throughout history is challenged to maintain this essential role at representing Nature-as-process – ‘To different ages are given different inspirations’. Via this feedback loop, Art can open us up to the myriad ways of experiencing and thinking through what Nature has become for us, and what we have become for Nature.

Please refrain from scrolling through LANDSHAPES.

Sit within it. Observe it.

And meditate with us on the nature of Art and the Art of Nature.

Written by Jeremy Kane

From the exhibition ‘ Landshapes’ by Amy Commins. 19th of March 2016.

Essay Courtesy of FAKE estate ARI.