Recently on a train I overheard some teenagers mocking the name of a station. “What a dumb word – what does Kuraby even mean?”

I knew what it meant. ‘Place of many springs’, a Bundjalung word. I had lived in the area for a long time and have fond memories of the creek that forms there, for which the site is named. But I’ve moved, and my new suburb has an English name, bestowed upon it through British colonisation andsymptomatic of the widespread decimation of Aboriginal languages.Through Megan Cope’s painting Twice Removed – Meanjin, I now know the area’s name was, is,Mahreel. But why is it only through Cope’s provocative artwork that I am learning this aspect of the area’s heritage?

The role played by language in the marginalisation of groups and individuals is paramount, in the various ways language is mobilised by an aggressor to assert dominance and enact oppression over another. In the abhorrent and protracted process of the systematic and fundamental disempowerment of Australia’s Aboriginal population, the erasure of centuries old languages is only one of many injustices carried out against Australia’s First People as part of the routine of British colonisation.

The British explorers and settlers went about recording the particulars of this previously ‘unfound’ land with a disregard for and obliviousness to the existing place names. Generally commemorating Europeanmonarchs, explorers, battles and noblemen, English labels were applied to the features of the Australian landscape;seemingly arbitrarily inscribing the presence of foreign British national heritage upon the land.Western naming claimed sites whereAboriginal names reference prominent natural features,reflecting distinctly different conceptions of ownership.

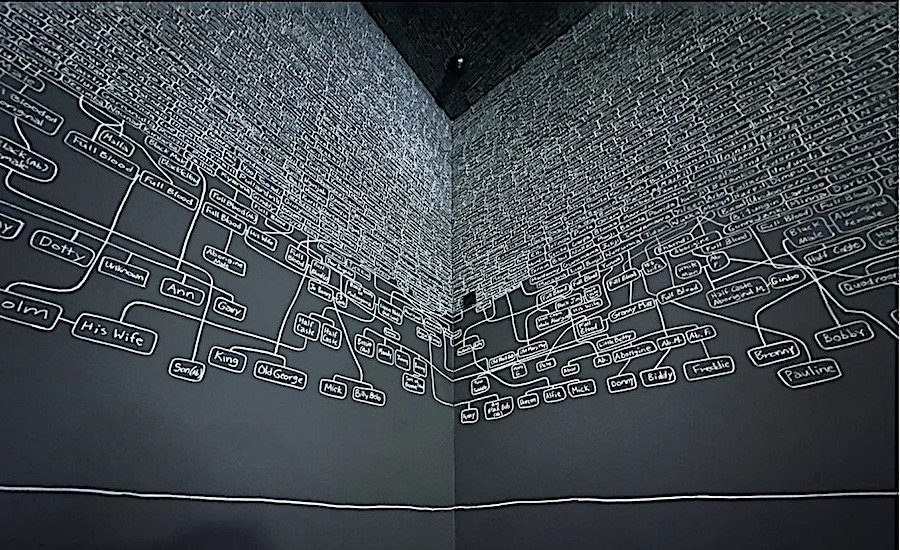

Boldly rendered in meticulous calligraphy, Megan Cope’s Twice Removed suite of paintings reassert the Aboriginal place names, marking themprominently over historical maps of the regions surrounding Brisbane, or rather Meanjin. A Quandamooka (North Stradbroke Island) woman, Cope has developed a complexpractice that focuses primarily on exploring the historical toponomy,cartography and geomorphology of significant locations. Cope’s use of parish maps commissioned by churches in the late 1800s and locality maps commissioned by the military in the 1940s are the basis for each work. This is an acutely calculated political statement that interrogates the power and privilege within these institutions, which generated a certain level of ambivalence towards Aboriginal people andownership of their own country.

In Twice Removed the five large scale circularpaintings depictlocations where the local indigenous population were forcibly displaced from or relocated to. In Beenleigh (Yugambeh) at the German Lutheran mission of Bethesda, on BribieIsland the reserve at Woorim and on North Stradbroke Island the Catholic mission atMyoraall used Aboriginal people as a source of cheap labour1. At Wynnum (Winnam) Black’s Camp became a gathering and camping site for those who’d been displaced, as did the Roma Street Parklands near the centre of Brisbane (Meanjin). Cope’s depiction of these historically loaded sites use the equally loaded maps authored by the very entities responsible for the repression and dislocation of Aboriginal populations. These serve as a sombre reminder of our nation’s history, and how the events of that past have led us to our current suburban geography.

Bridging time barriers further, Cope’s works go on to juxtaposethe familiar aerial landscapes of South East Queensland, replete with elegantly curved bay and snaking rivers, with the ominous impending environment of our future.In shimmering dot-work Cope engorges the waterways, applying a 5 meter sea level rise to the geography. The swollen bays and rivers of our post-climate change future are confronting images, with areas that today, in 2014, are built up with commercial and residential property decidedly underwater in Cope’s portrayal of the environment to come.

Cope’s work emphasises the fact that the landscape, and particularly the coastal landscape, is not a static entity. Coastal erosion is one of the many significant ecologicalchallenges of the twenty-firstcentury, particularly in Australia where so much of our population and infrastructure is based on the sandy edges of this vast island. Short-sighted colonial town planningcoupled with little to no action taken on climate change can only viably result in one possible outcome – not next week or next decade and not necessarily even next century, but certainly sea level will rise, coastlines will shift, and the environment will change.

Cope’s family have stories of a time when Moreton Bay was a valley, knowledge passed down through generations verbally and through art and music for centuries. Recently this information has been verified by scientists, who estimate the valley began flooding 18,000 years ago and reached it’s present state approximately 6,500 years ago2. Archaeological evidence shows Aboriginal people, Cope’s predecessors, were livingin South East Queensland at least 20,000 years ago at a conservative minimum3.

While there is no certainty amongst climate scientists as to exactly when we might experience a 5m sea level rise, there is a general consensus that we will see a rise of 50 – 110cm by 21004, a mere 86 years away. Considering Cope’s family hold in memory a time so long before the bay even came into being, to forecast the reality of the landscape as it might be in 500, even 5,000 years becomes less incomprehensible. It connotes a radically different attitude to that of Western progress regarding the perception of the natural environment, one that adapts to and embraces, rather than denies and resists, transition and change.

Through the simultaneous depiction of historical and future incarnations of Quandamooka, Winnam, Woorim, Meanjin and Yugambeh, Cope’s Twice Removed series serves as a reminder of the precarious nature of the relationship contemporary Australian society has built with our land and it’s First People. That history cannot be undone and hopefully will be eventually berepaired through genuine reconciliation.One aspect of that process is revaluing Aboriginal language and the place names they bestowed upon the land centuries before Europeans even imagined they could sail here.Artwork like Cope’s is an important part of this process,concisely articulating the circumstances of decades of past conflict and future ecological change that frame and face the Australia of today.

Written by Lisa Bryan-Brown

Footnotes

[1] State Library of Queensland (2014) ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander missions and reserves in Queensland’, accessed 3 July 2014, http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/82602/missions_and_reserves.pdf

[2] Walters, I(1992)‘Antiquity of marine fishing in south-east Queensland’,Queensland Archaeological Research 9:35-7, accessed 2 July 2014, https://www.library.uq.edu.au/ojs/index.php/qar/article/download/239/283

[3] Neal, R, Stock, E(1986)‘Pleistocene occupation in the southeast Queensland coastal region’,Nature 323, p 618-621, accessed 2 July 2014, http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v323/n6089/pdf/323618a0.pdf

[4] Australian Government, Department of the Environment (2014) Mapping sea level rise, accessed 3 July 2014,http://www.climatechange.gov.au/climate-change/adapting-climate-change/australias-coasts-and-climate-change/mapping-sea-level-rise

For more information please visit the – SGAR Website