Since the twentieth century the tradition of self-portraiture has been re-evaluated, making way for a new physical and psychographic assessment of the artist’s body in art1As a consequence, artists have increasingly employed their own body as both the subject and object of work. With the growing advancements of technology, this discourse is undergoing a vibrant resurgence and reassessment. We have entered a new age with the virtual mass production and representation of our personal image across various platforms; redefining our understanding and dialogue of self. This strategy has also achieved unprecedented prominence with blockbuster art projects such as Marina Abramovic’s The artist is present(2010).

Presence/absence surveys this resurgence of the artist’s body in art through its varying manifestations in the practices of six Brisbane artists: Louise Bennett, Athena Thebus, Clark Beaumont, Chris Bennie and Pirrin Francis. The exhibition explores the proposition and outcome of the artist’s body as the primary subject in work, equally surveying both its physical and implied presence. While ‘absence’ could primarily imply the invisibility of the artists body, Drew Lederarguesin The Absent Body that, ‘the notion of being is […] present in the very word absence’2. We need to have known the body existed, to recognise it is now gone.

Louise Bennett’s artwork strongly reflects this discussion of the presence inherent to absence. ‘I want to be here’ states Bennett’swork scrawled across the large glass pane of gallery’s front door. Positioned at the threshold of the gallery space, she openly shares this confession with the gallery viewer, while from the street the text is abstracted. Through this action, Bennett is expressing her desire to be in the white wall structure, functioning within its constructed paradigm. However, for the gallery viewer the glass pane acts as a transparent separation from the external world, juxtaposing Bennett’s confession against the suburban backdrop. The archway further frames the work in the outside environment; separate from the gallery she longs to be in.

Bennett’s statement ‘I want to be here’ plays upon the style and personal tone of status updates on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter. The hand written font references the low-fi, confessional and self-orientated statements that are common on these media platforms. This type of social networking dislocates civility and sociality, manufacturing a new type of digital narcissism3. Users share every thought, want and wish, through repetition and mass these statements become disposable or even cliché. Bennett’s statement is genuinely sincere, she wants to be in the gallery and wants to share this with the viewer. However, as she has consciously placing herself at a liminal position to the gallery, her words in the context of this style are removed; becoming a throw away or over trivialised gesture.

Athena Thebus’s work also takes cues from the virtual world. Thebus’s practice makes use of a commonly recurring symbol throughout her practice, in a manner that pays homage to the ‘selfie’ or a Hollywood headshot. She plays on the contemporary obsession with the attainment of fame. As discussed in Vanity 21st Century Selves reality television, social media and blogging make the western ideal of celebrity and glamour seemingly achievable3. This process of virtually sharing and promoting your image mimics the actions of aspiring actors carrying around headshots and handing them out at the sign of any faint opportunity. The artwork .410 Headshotz plays on this notion by displaying two images, one is the original photograph and the other an edited version in which Thebus has airbrushed herself; removing any red spots or pimples on her face and whitened her teeth and eyes. Thebus’s repetition of the self across her work transforms her image, making it an icon or a representation of self that is removed from her body similar to that of an avatar. The growing occurrence of the ‘selfie’ in social media platforms has aided in the construction of a new dialogue where the individual becomes their own online avatar8; an overarching immobile expression of who we are.

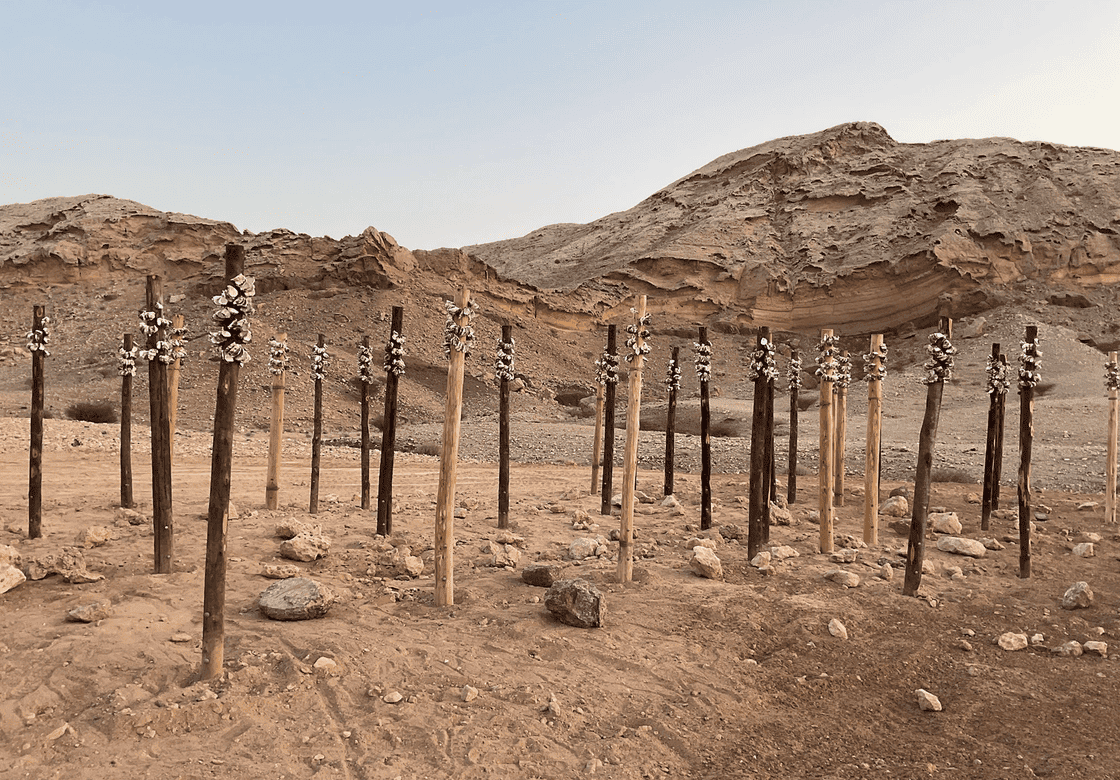

After printing, Thebus sent these two images to a friend on a cattle property to shoot them with a .410 gauge shotgun. This could be read as a critique of the self or the strive for fame and digital enhancements. In conversation Thebus gave rise to the idea that this is also a play on the prevalence of violence in our generation in the western world and how we are desensitised from its impact. We come across it online and just scroll past it, ultimately unaffected by its prominence.

Similar to Thebus’s investigation of self, Clark Beaumont (the title of the collaborative practice of Sarah Clark and Nicole Beaumont) utilise the physical presence of their bodies as a key-defining factor throughout their work. Instead of employing the face as an icon of self they utilise their whole body and interactions to investigate ideas and constructs around identity, female subjectivity, intimacy and interpersonal relationships. Clark Beaumont’s artwork Hold on to that Feeling is a dual screen video installation in which Nicole and Sarah perform a durational pose. Their stance is an appropriation of Judd Nelson’s character at the end of the infamous ‘80s film, The Breakfast Club. Referencing screen culture, Clark Beaumont utilise the body in this artwork as a site for the discussion of masked or performed gender. As raised by Courtney Pedersen in a recent essay on Clark Beaumont’s work, this action can be interpreted as either ‘manning up’ or ‘dropping the masquerade of womanliness’4. As Judith Butler infamously discussed in her book Gender Trouble the concept of gender is a reiterated social performance rather than a predetermined reality; any person can adopt the mask of ‘masculinity’ or ‘femininity’5.

Chris Bennie has a different approach concentrating on significant social interactions or observations of his surroundings. Utilising video and photography to document his subjects and search for ways to make them meaningful, he concentrates on their framing and transformation into an artwork. Across his practice, Bennie often concentrates on his body undertaking obscure tasks or interacting in the home environment. In ‘The Western Fields’ his presence is inescapable, but implied, you are aware that he isin the work, while his physical self is left outside the camera frame. As Philip Auslander discusses in his book Liveness, ‘It may be that we are at a point at which liveness can no longer be defined in terms of either the presence of living human beings before each other or physical and temporal relationships […] The emerging definition of liveness may be built primarily around the audience’s affective experience’6. While Auslander makes this statement regarding performance and the liveness of websites, this is relevant as Bennie’s existence is prominent outside of his physical manifestation. Bennie’s presence is evident whether he is physically interacting within the home environment or he is behind the camera, obscurely driving a car around a shopping centre car park; we equally know he is there dictating the scene.

While the other exhibiting artists concentrate on the present self, Pirrin Francis observes her body through the past. Utilising home videos, photographs and memories, Francis concentrates on her relationship with her childhood self. Francis’s work At the Cusp of Sleeping displays a video of a baby’s face, abstracted from its body through a frame-by-frame editing technique. The use of edited family footage in the work forges a relationship with the viewer, evoking a sense of nostalgia. Debra Porch further highlights this relationship stating, ‘objects and visual devices incorporated in art installations can function as triggers that retrieve memories and images from one’s past’7.The baby’s face moves fluidly across the wall as a solid entity abstract from its body; the infant becomes omnipresent, a universal representation of a baby. This relationship between the visual device and nostalgia allows Francis’s body to become a platform for the viewer to project their own past experiences.

With the growing influence of social media and the occurrence of the ubiquitous ‘selfie’, ‘photography has become part of a daily, if not minute-by-minute, staging of the self’8. This process has redefined the contemporary understanding of the body and self. This has both directly and indirectly reinvigorated this concept in the work of these artists. The contemporary exploration of the body and self can be equally explored through both physical and implied presence. After all, to recognise something is gone, we have to have known it existed. By noting absence, we paradoxically affirm the power of presence.

Courtesy of Spiro Grace Art Rooms

Image Credit: Carl Werner

References

- Jones, A., & Warr, T. 2000. The Artist’s Body: Themes and Motives. London: Phaidon. p. 11.

- Leder, D. 1990. The Absent Body. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. p. 22.

- Tanner, C., Maher, J. & Fraser, S., 2013. Vanity: 21st century selves. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Chapter 5.

- Pedersen, C. 2014. Feeling it out, exhibition catalogue, 10 January – 1 February, Kings ARI, Melbourne, Vic.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

- Auslander, P. 2008. Liveness. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge. p. 62.

- Porch, D. “The Visible and the Invisible: Connecting Presence and Absence through Art, Memory and the Body.” PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology. p. 18-19.

- Allen, J.2011. “Who me?” Frieze Magazine (143). Accessed February 7, 2014 http://www.frieze.com/issue/article/who-me