The story goes:

As a child, D discovered a Zero fighter plane crashed in the bush behind her house. The wings were beat up, the nose was crumpled and banksias had started growing through the cockpit. The plane was practically pungent with history; a skeleton cast from the bombing of Darwin Harbour, a relic from one of the largest airstrikes on Australia. But for D and her sisters, the plane simply became one very cool cubby [1].

Narrative weaves precariously in and out of Anya Swan’s practice. Yet while her works are tied to reality they hover on the verge of mystery and absurdity; where the discrepancies between fact, fantasy and emotion bleed messily together.

Anya paints, draws, pulps paper, molds and seals eerie figurative-esque paper forms with resin. Her works are rarely smooth; they appear to bubble, pulsate, sway and they represent and distort familiar imagery, unpacking our rituals and parameters for the everyday. In presenting us with overtly hand-made, ad-hoc objects Anya permits her narrative frameworks to swell and dissolve, implicating viewers in-between states of representation and subjectivity. And it’s these shifting states that she uses as allegories for the complex and precarious realms of ‘inter-personal exchange’.

Anya mentions that her works start with stories about ‘people interacting with each other’ and their vignette, model-like properties propose birds-eye-views and third person perspectives. At times these perspectives, when combined with bodily references and textures, alternate viewers between feelings of watching and being watched. Her choice of imagery also enhances this feeling of unease through her tendency to depict figures and forms as un-rendered, isolated and estranged. I have seen Anya present an array of lone caricature-esque figures and forms; one awkwardly holds a green baby; another is despondently wrapped in a bath towel, garden hose in hand. I’ve also noticed skewed bat formations (and other animals displaying human-like characteristics), an empty public pool and lumpy floating boxes.

‘you me and a weirdo’ revolves around a larger aeroplane relic, carefully painted and assembled to give appearances of age and injury. It rests in the gallery, much like an aquarium ornament on the bottom of a fish tank. This makeshift model, even in its playful, hand-made state, reeks of time’s relentless melt, of things left unkempt and the way tragedy and the unresolved nature of death are inevitably things that haunt. For me this work is both playful and serious. It collapses personal and political arenas but with an uncertain smile. While inspired by a second-hand ‘truth’ Anya’s rendition moves beyond specific bodies and lips to emulate frictions between the sculptures own process and intent and conflict narratives more broadly. And while these themes are left in flux, we’re marooned within our own detachment; at odds and unable to follow our habitual desires for order and resolve. And in encouraging us to re-position ourselves Anya asks us to think for ourselves, promoting speculative interpretations that prolong experience rather than over-encode or stifle it. And I think her clunky, formless techniques play a star role in all this; her textures and application delightfully and noisily repel and intrigue, delude and persuade. They ask us to be wary, but of what I’m never sure. I speculate it could be the freedoms but also the dangers of swimming outside the flags? Or she might hint at how insidious and all-encompassing the nature of misunderstanding is; and the way it can dangerously haunt and infiltrate not only the borders of our media and technologies, but that of our bodies and minds.

And meanwhile I discover:

The plane was unlikely a zero fighter (only a small number were reported missing and most have been accounted for). The plane that most likely fits the description is an Airspeed Oxford, as the RAAF had a heap of them, a couple went down over that area, from what D remembers (door on the side/gear inside) it’s the most likely of the planes that also match that description [1].

I saw Kate Tempest interviewed on ‘ABC’s the mix’ and as a poet/musician she connects her interests to ‘ideas of cycles and loops’ and that ‘in a hip-hop sense these loops become the mantra’. She concluded by describing looping as a ‘process of retracing the cycles themselves, and that part of getting older is to spot the cycle before you find yourself unwittingly back on it; in terms of behaviors or situations or relationships’ [2].

So I imagine Anya is finding methods for interrupting and redirecting the ‘loops’ in our lives. And while standing here gazing at a paper mache aeroplane and a series of stiff mutated bats, hopefully we start to ask ourselves: what are our own realities made up of? where do they come from? and to what end? And most importantly, are they our own?

And I guess that’s why ‘weridos’ haunt our minds and conversations; they can’t be contained because they depend on who ‘you’ or ‘I’ are; and in being essentially everything ‘we’ are not, they are home to our fears and lack of understanding.

Written by Erika Scott

- Swan, A, 2016. Personal email correspondence [between A. Swan and E. Scott]. [1‐16 June2016]

- ABC The Mix: News 24 view. (2016). Kate Tempest speaks with Zan Rowe on ABC’s The Mix. [Online Video]. 18 May 2016.Available from: Link. [Accessed: 8 June 2016]

Essay from the exhibition ‘you, me and a weirdo’ by Anya Swan (July, 2016). Courtesy of Fake estate ARI

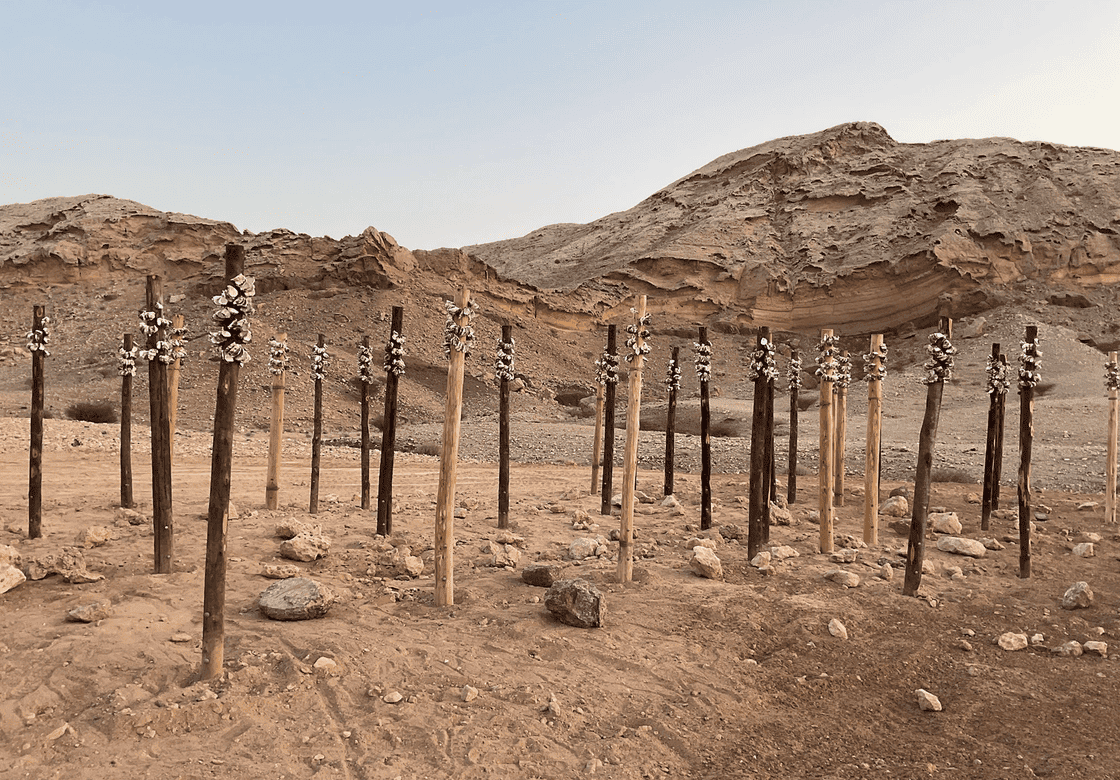

Image: anya swan, bat rack I, 2016